Disclaimer: Views in this blog do not promote, and are not directly connected to any L&G product or service. Views are from a range of L&G investment professionals, may be specific to an author’s particular investment region or desk, and do not necessarily reflect the views of L&G. For investment professionals only.

The return of Realpolitik – and what it means for investors

In 1990, Francis Fukuyama declared the “End of History” in his eponymous book, foretelling the end of ideological strive and the spread of democracy throughout the world. If this era is over, what could replace it? In this blog we hypothesise that the world is returning to great power competition with important implications for investors.

Over the past 35 years, since the fall of the Berlin Wall, liberalism has been the dominant paradigm in international relations. It posits that the interests of liberal democracies are best served by promoting their governance model globally.

Liberal democracies, so the belief goes, are less likely to start wars. For example, in most commentary, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is blamed on the authoritarian tendency of its government.

Another tenet of the liberal paradigm is that countries that trade with each other are less likely to go to war. This was Germany’s main line of defence, when criticised for the pursuit of Nord Stream 2, even after Russia’s annexation of Crimea.

Furthermore, countries that develop through trade will eventually become liberal democracies. This was the main motivation behind the US decision to admit China to the WTO. By giving China a stake in the US-sponsored order, it was hoped, China would become more like the US.

International organisations, like the UN, EU or WTO, are seen as key conduits to extend the liberal-democratic order. At times, even wars can help spread liberal-democratic ideas, as attempted in Iraq and Libya.

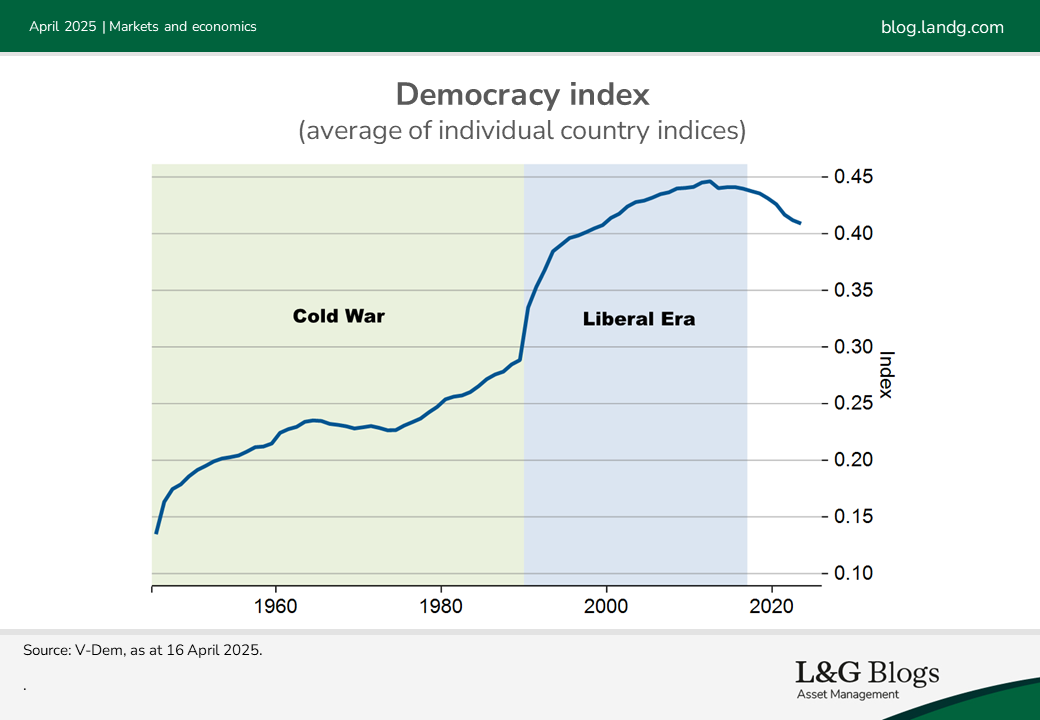

The liberal paradigm in international relations has been discredited. Russia and China did not become liberal democracies. Russia’s integration into the global economy did not prevent it from attacking Ukraine. Neither did China’s accession to the WTO prevent it from bullying its neighbours. The wars in Iraq and Libya were failures. While the initial spread of democracy was impressive, this development appears to have gone into reverse since about 2012.

A cold, indifferent world

What could replace the liberal paradigm? A realist approach to international relations. Realism has a long tradition, including thinkers like Thucydides, Machiavelli and Hobbes. One of the strongest recent formulations in our view is ‘Offensive Realism’ put forward by John Mearsheimer, a University of Chicago professor of international relations.

Offensive Realism is based on three key assumptions:

- The overriding objective of every state is security and survival

- There is no superior authority at the international level

- States cannot be certain of the intentions of other states

From these assumptions flow a number of sobering potential consequences:

- States pursue power at the expense of other states. They don’t do this because they are intrinsically aggressive, but because it is the only way to ensure survival in a world without an ultimate arbiter.

- Great powers strive for regional hegemony and try to prevent regional hegemons elsewhere. They would strive for global hegemony, but the stopping power of water makes this impossible.

- States pursue other objectives besides power, for example, moral or economic objectives. However, when those other objectives come into conflict with power competition the latter always takes precedence. After all, objectives are moot without survival.

- All states behave in this manner, irrespective of their form of government. This is a big departure from the liberal notion that democracies are less aggressive than dictatorships.

- Finally, international organisations serve the interests of the most powerful state. They have no independent effect on state behaviour and are not instrumental in securing peace.

Realism offers a chilling account of how the world works at the international level. Unfortunately, there is some evidence to support it. That power competition trumps values is apparent in the US’ embrace of dictators during the Cold War. Similarly, the recent US rapprochement with Russia, despite the atrocities of Bucha and elsewhere, owes much to the larger rivalry with China. Europe on its part remains silent over Erdoğan’s jailing of his rival, as Turkey is needed to contain Russia.

With respect to international institutions, the US never joined the International Criminal Court and followed WTO rules until it didn’t. Both Germany and France broke European fiscal rules when it served them. Also, out-of-sample Offensive Realism performed rather well.

In 1993, John Mearsheimer urged Ukraine to keep its nuclear weapons.[1] In 2001, the year China joined the WTO, he predicted that China would not rise peacefully.[2] In 2014, Mearsheimer insisted that NATO’s expansion to Ukraine and Georgia risked war with Russia.[3] His 1990 prediction that NATO would disintegrate did not come to pass but looks prescient today.[4]

Why was realism not fashionable during the past 35 years? After the collapse of the Soviet Union the US was supremely powerful. In this unipolar world, the US and its allies could afford to pursue noble ideals. Meanwhile another great power has appeared on the world stage in the form of China. Hence, great power competition is back.

Interpreting the US in 2025

Realism could go some way in understanding the policies of US President Trump. This is because some overlap exists between realism and a nationalist agenda marked by tariffs, secure borders and ‘America First’.

Both realism and nationalism see the nation state as the key actor and point of refence. By contrast, liberalism takes the individual as starting point. Also, both realism and nationalism put own welfare above others’ welfare. Liberalism on the other hand is universalistic endowing individuals with unalienable rights, irrespective of origin.[5] There are of course differences. Nationalism is a real-world phenomenon, while realism is a theory to explain and guide state actions.

Implications for investors

In the Asset Allocation team, we believe diversification[6] can help to act as risk management by design, ensuring we are not overly exposed to any one asset class, region, government or economic scenario. As a matter of process we often consider different scenario’s to map out how the future might look like.

We therefore believe the framework of Realpolitik will help us to plan ahead and manage risk better for clients. For instance, it helps us to better understand questions like:

- Why are international organisations like WTO and NATO under pressure?

- Why do tariffs, secure borders and America First becomes vote winners?

- Why do domestic industries like shipping, steel, industry, information technology and energy start to matter much more in the eyes of politicians?

In this vein, the shift in geopolitical paradigm has important implications for investors. For starters, power competition trumps economic considerations. Many people, including us, ruled out a Russian invasion of Ukraine on the grounds that it did not make economic sense. We were probably right about the economic costs, but our end-of-history mindset was too narrow in scope.

Similarly, people dismissed the possibility of high US tariffs, given the cost to the US economy (we didn’t). What matters in a world of great power competition is whether tariffs hurt China more. The same holds when considering whether China might sell its US treasury holdings. It will hurt China, but will it hurt the US more?

Second, some believe democratic backsliding may be irrelevant for investment returns. Autocrats may not be sanctioned if they help the balance of power. Therefore, what is right and what makes money may not be as neatly aligned as it was in the past. People may still want to demand an ESG approach, but it could be more important than ever that such strategies are based on a robust of assessment of material financial risk.

Might the EU begin to break up? If the US withdrew from Europe to focus on Asia, might power competition between its big powers make a comeback? Which assets would be most at risk? The answer is not straightforward. The threat from Russia may prove a strong centripetal force. Also, the US may determine that a strong Europe helps in its rivalry with China. Nevertheless, a breakup can no longer be dismissed outright.

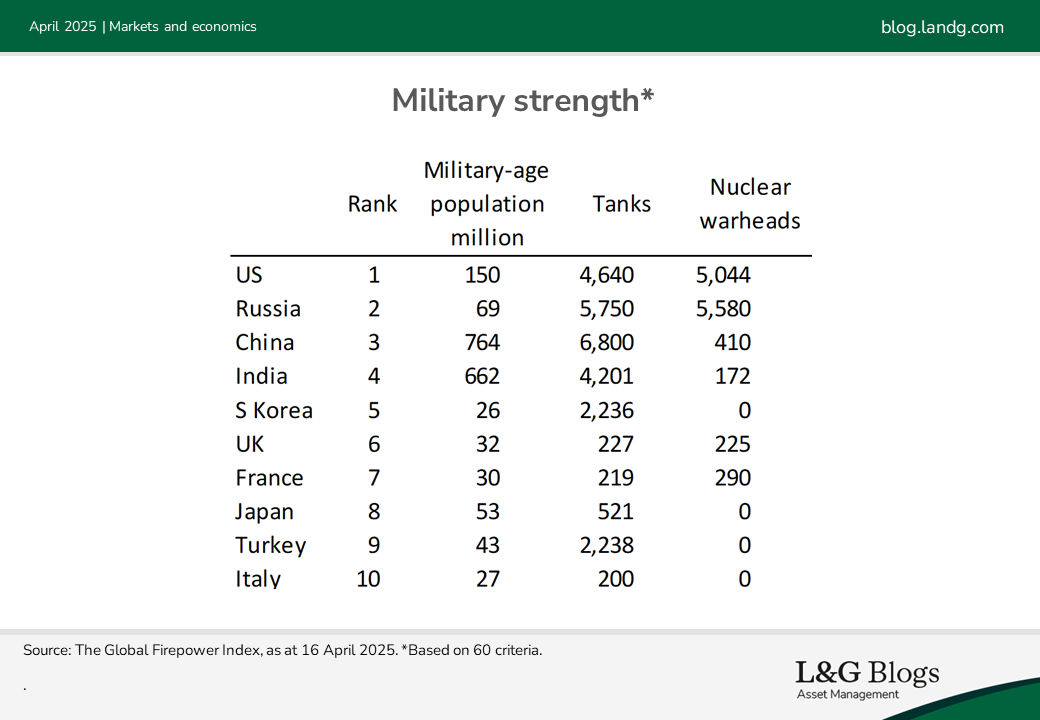

Which countries matter for great power competition? Russia, being the third great power, besides China and the US, may matter the most for balance of power considerations. Turkey matters due to its geographical location, while India matters for its size. Latin America, already firmly in the US sphere of influence, matters little. While Japan, Korea and Taiwan matter, they are also particularly vulnerable in case of conflict.

Which sectors matter for great power competition? Shipping, steel, industry, information technology and energy matter a great deal. Not surprisingly, they are at the centre of recent trade policy. Consumer goods, cars and services on the other hand do not matter.

If all of this sounds vaguely familiar, it’s because it is. History never ended; it just took a breather over the last 35 years. Being clear-eyed about it as investors will be crucial.

[1] Mearsheimer, John (1993) The case for a Ukrainian nuclear deterrent.

[2] Mearsheimer, John (2001) The tragedy of great power politics.

[3] Mearsheimer, John (2014) Why the Ukraine crisis is the West’s fault. In 1998, Mearsheimer predicted that NATO’s Eastward expansion risked war with Russia (Now a Word from X, The New York Times, May 2, 1998).

[4] Mearsheimer, John (1990) Back to the future: instability in Europe after the Cold War.

[5] Mearsheimer, John (2011) Kissing cousins: nationalism and realism, unpublished manuscript, https://www.mearsheimer.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/kissingcousins.pdf

[6] It should be noted that diversification is no guarantee against a loss in a declining market.

Recommended content for you

Learn more about our business

We are one of the world's largest asset managers, with capabilities across asset classes to meet our clients' objectives and a longstanding commitment to responsible investing.