Disclaimer: Views in this blog do not promote, and are not directly connected to any L&G product or service. Views are from a range of L&G investment professionals, may be specific to an author’s particular investment region or desk, and do not necessarily reflect the views of L&G. For investment professionals only.

T-bill stakes: finding buyers and sellers

Treasury ownership has changed significantly since discussion of the ‘balance of financial terror’ 20 years ago.

It was a pleasant scene but an ominous message. Amid the lush setting of the White House Rose Garden, President Trump delivered a proclamation to the world of sweeping tariffs. In subsequent days, equities responded with horror, sharply dropping amid the greatest change to the global trading system since WWII. The market’s fears were realised: Trump’s re-election as president carried still-more tariff risk than had been faced before.

But this crisis atmosphere was different in one crucial respect: US bonds sold off. The US 10-year yield, although dipping to below 4% in the days after liberation day, then jumped sharply by over 60 basis points in four days, the opposite of how the treasury market is supposed to behave. Although tariff policy is now easing, discussion has since raged about what the debacle might imply for global dollar dominance, and the implications for the treasury market.

With a new world order asserting itself in global politics and finance, how at risk is the treasury market and other dollar assets? In this two-part series, I examine the ownership structure of US treasuries, assess their potential alternatives, and discuss the potential for a grand bargain under the aegis of a ‘Mar-a-Lago Accord’.

We’re not in the 2000s anymore

Much of the popular anxiety around US treasuries stems from the so-called ‘balance of financial terror’ whereby foreign investor predominance in the US treasury market gives foreign governments (usually China) substantial leverage over US policy. This impression is likely overstated.

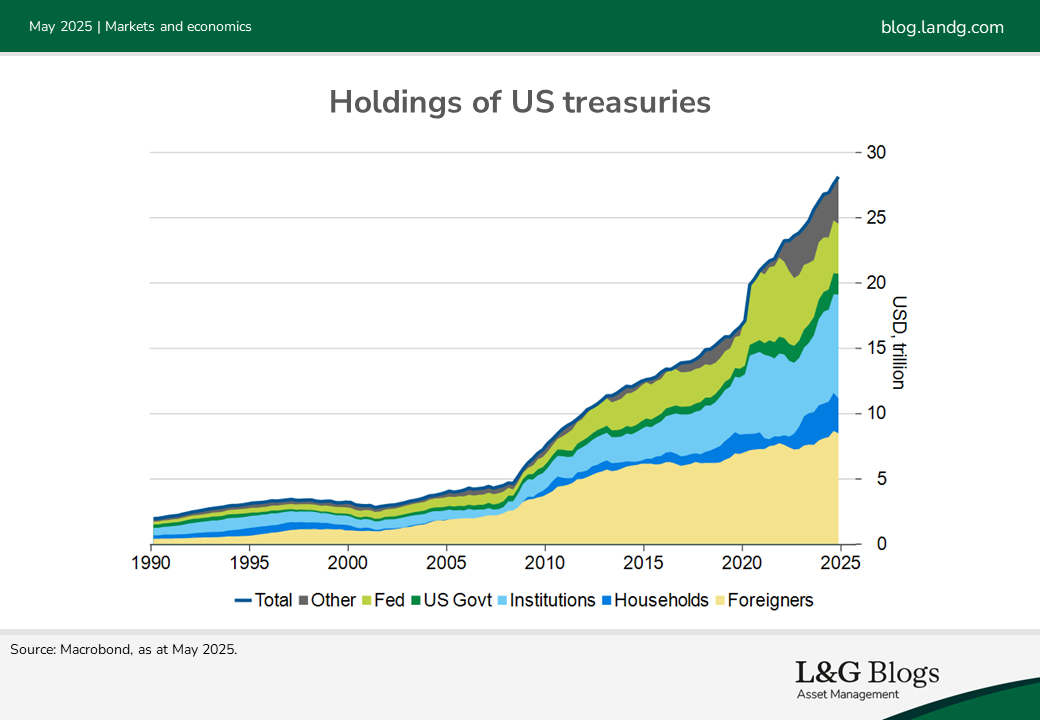

Since the financial crisis, treasuries have since seen remarkable ‘indigenisation’ of exposure, with foreign investors owning a much smaller share of US bonds than back in 2008. Whereas foreign officials might have owned a large share of treasuries 20 years ago, much of the issuance now is held by US-domiciled institutions.

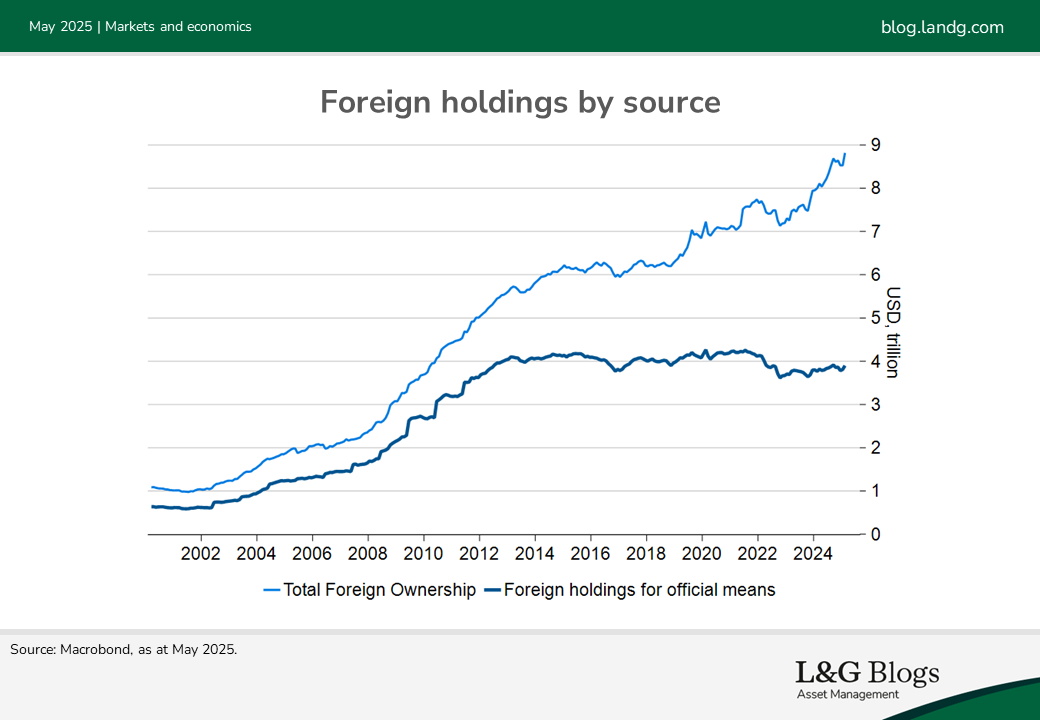

Even among foreigners, the new holder of US debt is very different. Whereas back in 2005, about 80% of all foreign-owned treasuries were owned by so-called official accounts (typically central banks), nowadays non-official holders (like banks insurers and other financial vehicles) hold more treasuries than official ones.

While these offshore treasury holdings are closely watched by government officials, thereby giving foreign governments some degree of control, these larger private holdings should give those anxious about foreign control of US debt some relief. Although persistent external deficits certainly mean the US depends on foreign financing, American dominance over the global financial system still gives her substantial headroom.

Absorbing an issuance monsoon

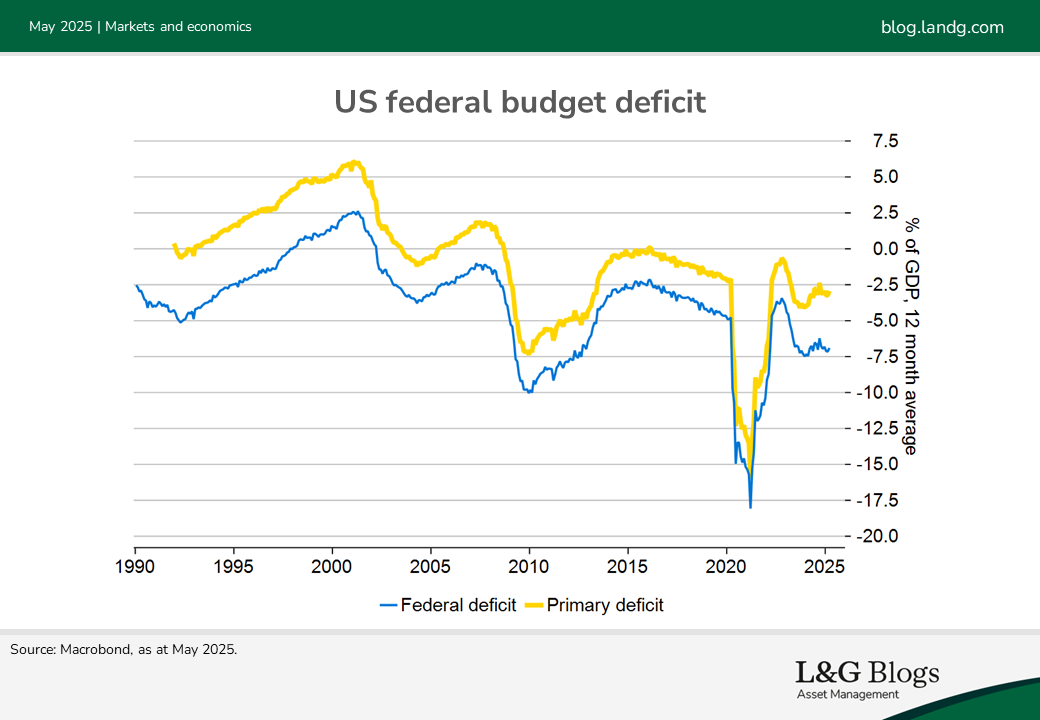

If treasury dominance is not ended by foreigners ditching T-bills, some caution it could end by a rapid breaking of US fiscal credibility. It’s true the US deficit stands at roughly 7% of GDP, an eye-watering total, and the debate around the US tax bill highlights how policymakers are talking on fiscal largesse at a leisurely pace. Swelling costs associated with Medicare and Social Security as the population ages are also set to inflate the deficit still further in coming decades. Might the wave of issuance prove too much to bear for the treasury market?

Yet the evidence for a sharp breakdown is less solid than it first appears. On the external side, IMF forecasts of the growth of current account surpluses among creditor countries (typically reinvested in US treasuries) is set to outpace projections of issuance over the next five years. This should give external demand for treasuries some ballast.

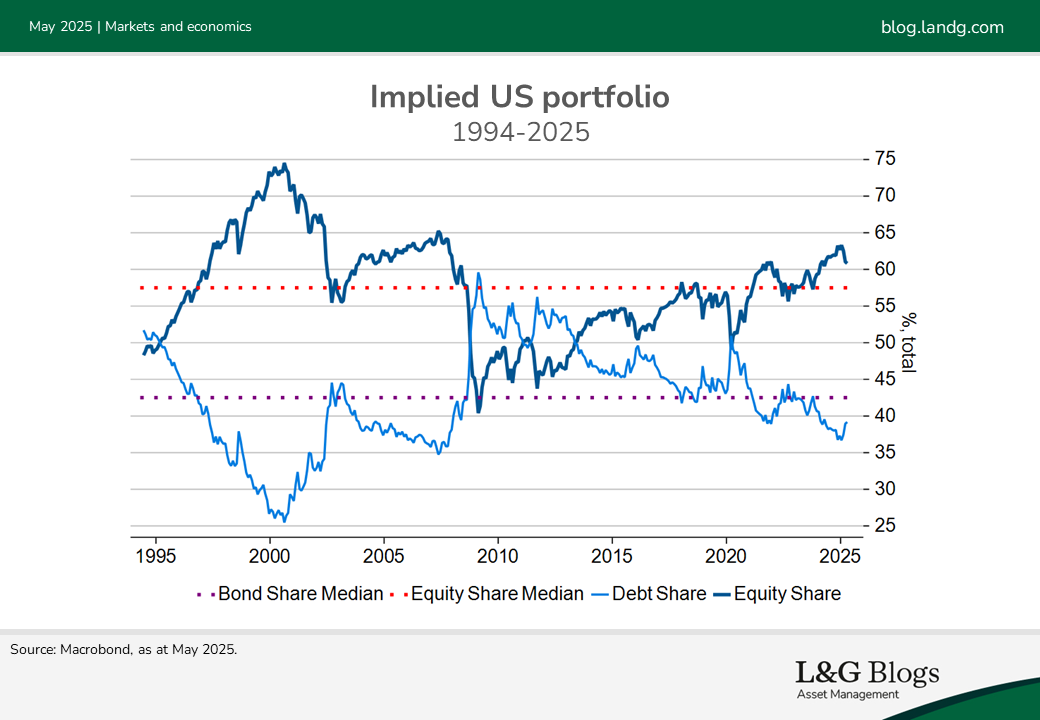

Domestically, policy organs like the Federal Reserve have rapidly normalised their treasury holdings since end-2021 and can always slow the pace of their asset-shedding to keep treasury markets functional. Lastly, looking at US asset shares, there remains some space for diversion in US assets from equities into debt, as the implied equity weight in US public markets remains much higher than its historic median.

Although President Trump’s pyrotechnics in the Rose Garden might give investors some pause about exposure to the treasury market, the key domestic anchors of US treasury dominance remain in place.

This is the first of two blog posts covering the US treasury market; the second instalment will discuss any potential alternatives to US Treasuries.

Recommended content for you

Learn more about our business

We are one of the world's largest asset managers, with capabilities across asset classes to meet our clients' objectives and a longstanding commitment to responsible investing.