Disclaimer: Views in this blog do not promote, and are not directly connected to any L&G product or service. Views are from a range of L&G investment professionals, may be specific to an author’s particular investment region or desk, and do not necessarily reflect the views of L&G. For investment professionals only.

How could uncertainties around US policy impact emerging markets?

The new administration in Washington is pursuing radical changes to global trade – what consequences could these have for rising economies?

The Trump administration is instituting policy changes that will have far-reaching implications for much of the world. They span the US’s domestic economy, society and foreign policy, and they are likely to have consequences for the macro outlook for emerging markets (EM).

While the early months of the administration has shown that policy decisions can be fluid, should public proclamations of intended US policy changes translate into action and remain in effect for a sustained period, there are four main areas they’ll likely impact:

1. Trade

2. Aid

3. Remittances

4. Changes in the outlook for US growth and inflation.

In this article, we’ll consider each of these in turn.

Trade and tariffs

From the mid-1980s on, there was a rapid reduction in international trade barriers. Emerging markets benefited massively, with many countries establishing themselves as strong exporters, particularly in Asia. However, the last two decades have seen important changes in the dynamics surrounding this trade growth.

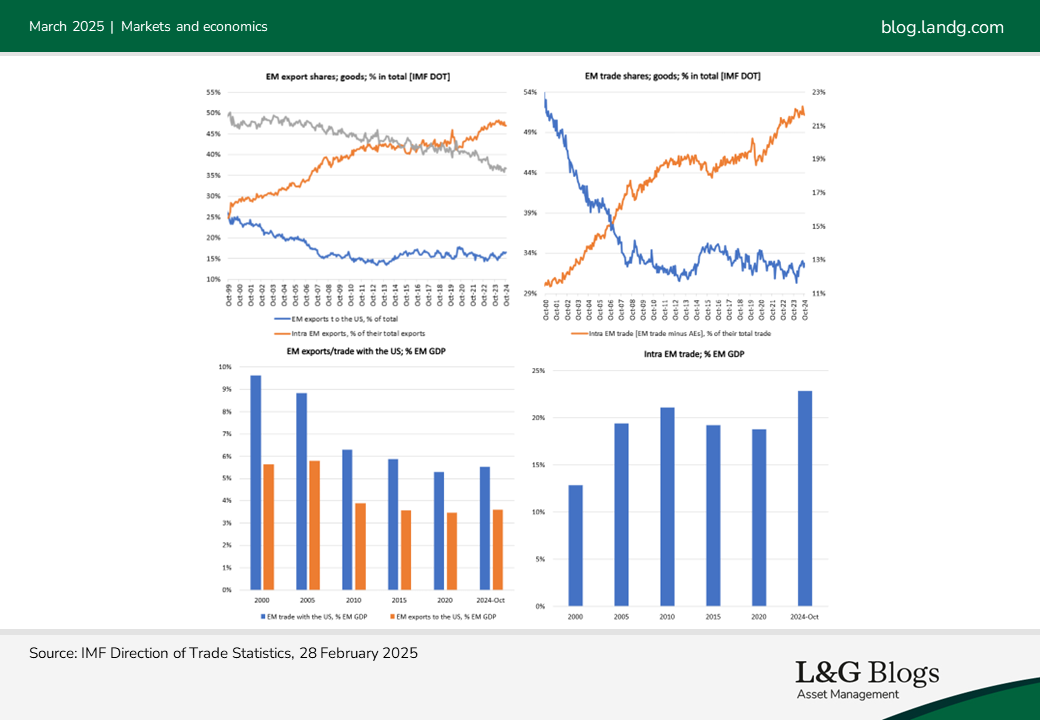

The importance of the US – and advanced economies in general – as the destinations for EM exports has declined, while trade between emerging markets has grown. As the charts below show, in the late 1990s/early 2000s, as much as 75% of EM exports went to advanced economies including the US, which alone accounted for a quarter of this figure.

Fast forward to now and almost half of EM exports, and trade overall, is between themselves. Trade with the US has declined in its significance for the EM economies, while the importance of trade between emerging markets has increased.

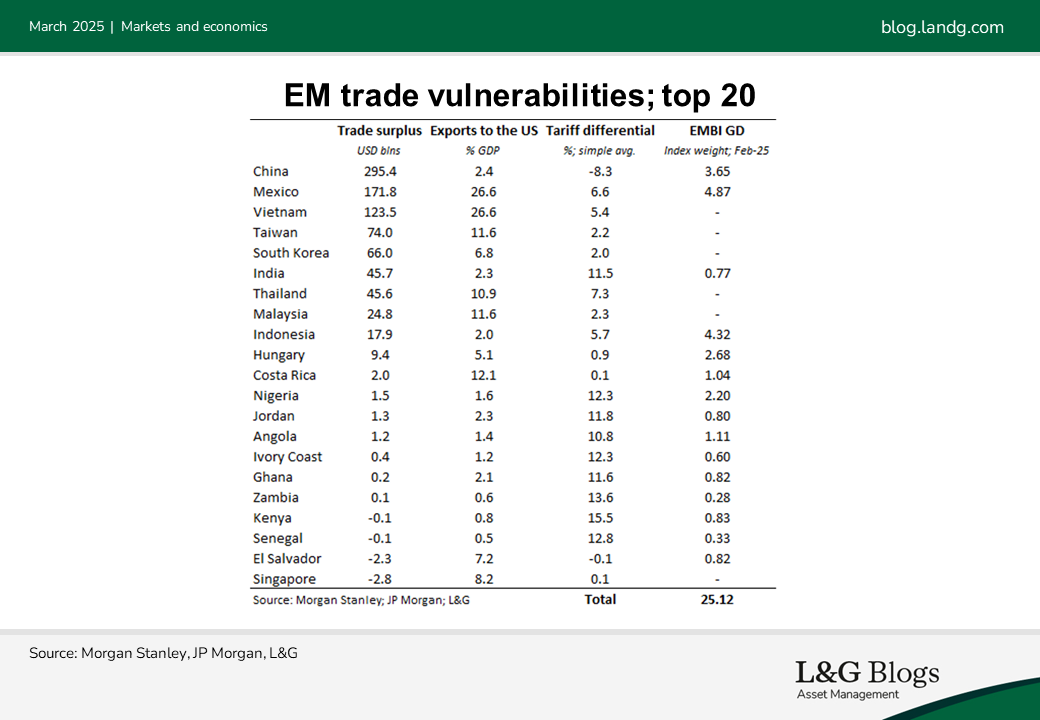

While risks posed to emerging markets by US tariffs have declined at an aggregate level, the picture is more mixed at a country level. Looking at the table below, and bearing in mind the still uncertain outlook for tariffs and trade, emerging Asia and Latin America appear most vulnerable given the large share of their exports to the US. African countries are also vulnerable, given large tariff differentials with the US. Looking across the emerging markets most vulnerable in terms of trade and tariffs, we estimate they account for a quarter of benchmark indices.

US bilateral aid

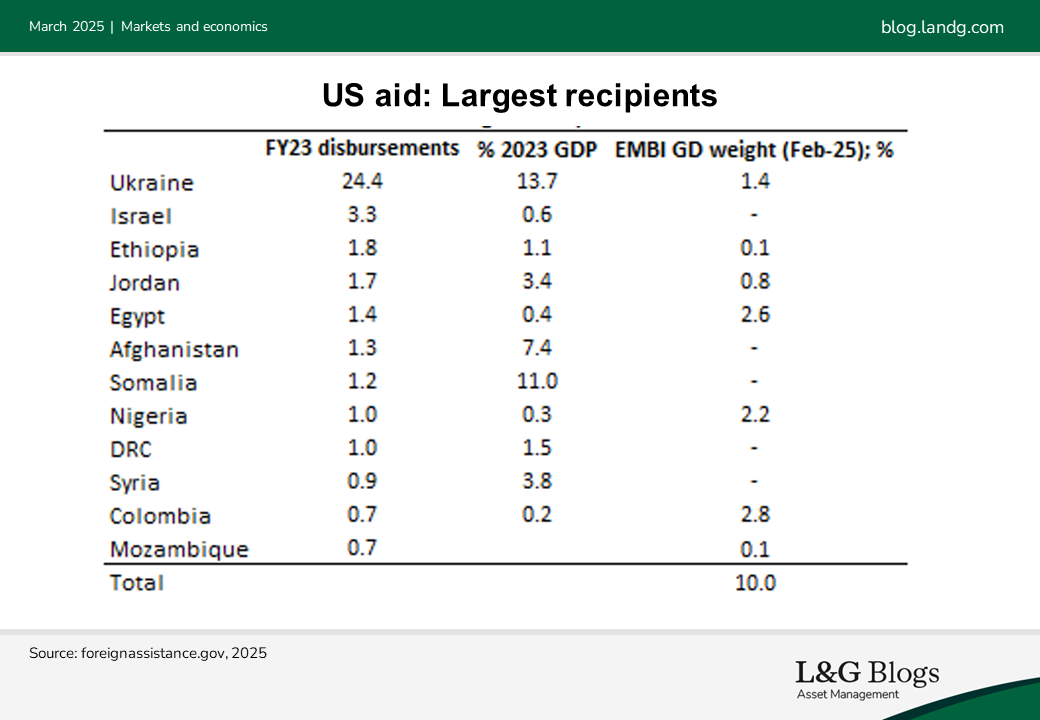

A second source of vulnerability for emerging markets arises from the US’s mooted suspension of bilateral aid. The US is among the largest sources of aid, channelling some $80 billion in 2023 to emerging markets via various agencies and programmes[1].

Notwithstanding the large absolute dollar amount relative to other bilateral donors, at an aggregate level the support provided is relatively small at just 0.2% of EM GDP in 2023 (our calculation, based on GDP data from the IMF). Even at a disaggregated level, and if we disregard Ukraine, US aid provided to countries with traded external debt is relatively small, as detailed in the table below.

Remittances from the US

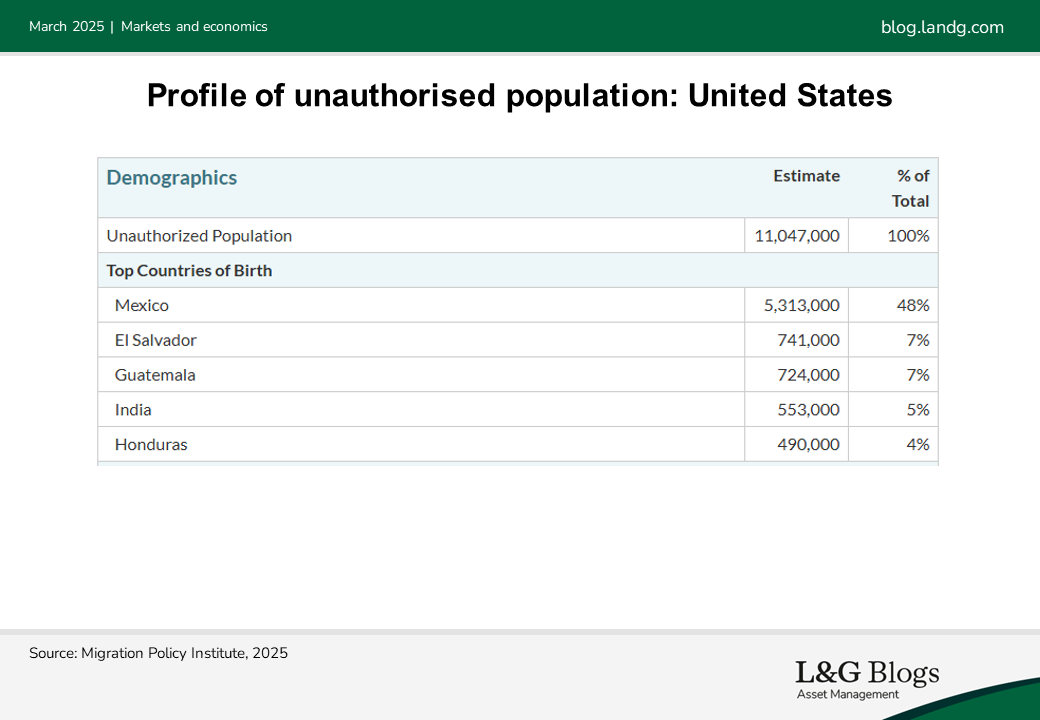

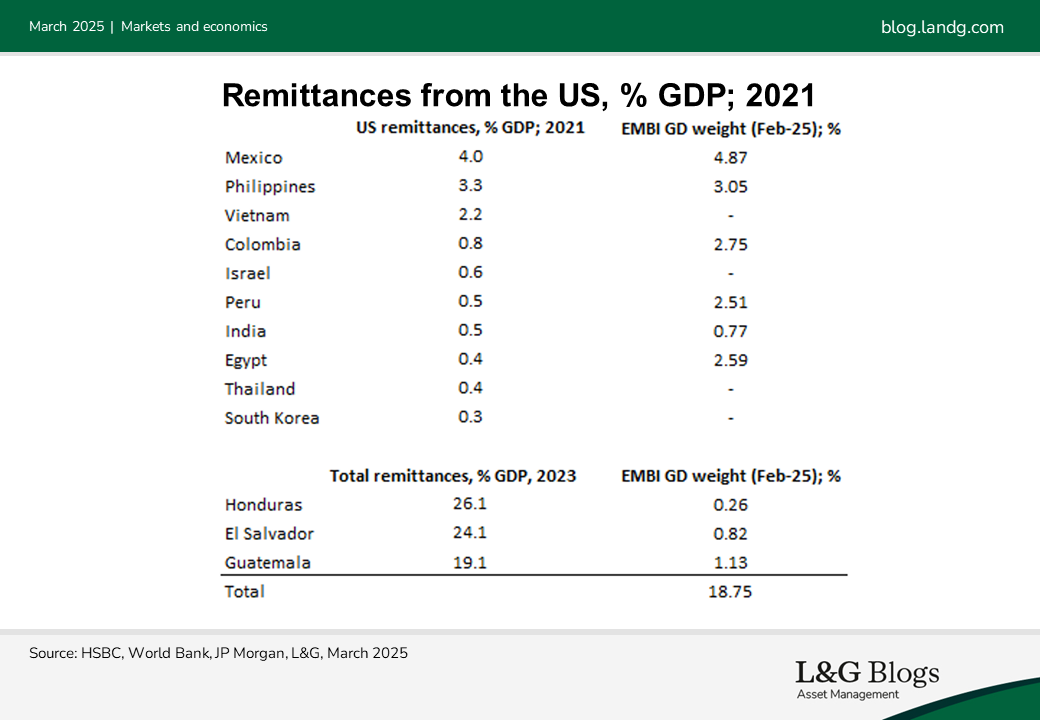

EM external financing needs could also rise in some emerging markets thanks to plans to deport as many as 11 million undocumented migrants from the US. Data from the Migration Policy Institute presented in the table below suggests a heavy skew to Mexico within the unauthorised population.

The above data covers 70% of the estimated migrant population. In the table below, we also include other countries which receive significant remittances from the US. It is conceivable that some part of the migrant population from these countries is undocumented.

Although there are significant uncertainties (including logistical and potentially legal challenges), should the Trump administration be successful in executing its deportation policies, some of the countries below could see lower remittances, and – all else being equal – larger external financing needs.

EMs economic strength

However, whether it’s the decline in aid or remittances, there are several mitigating factors.

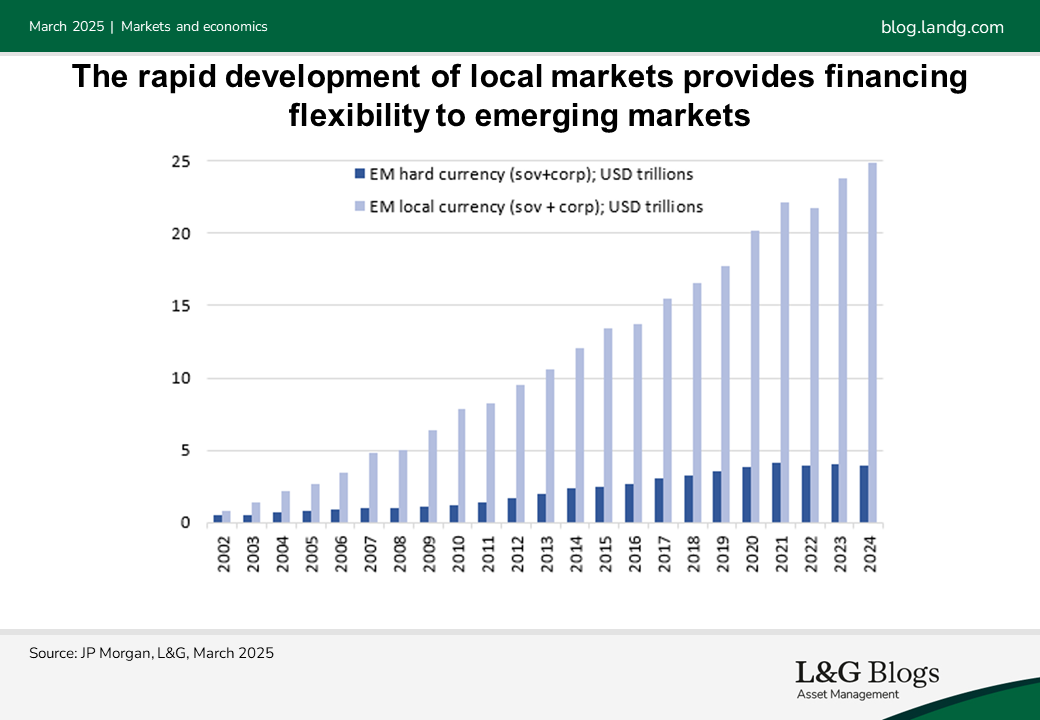

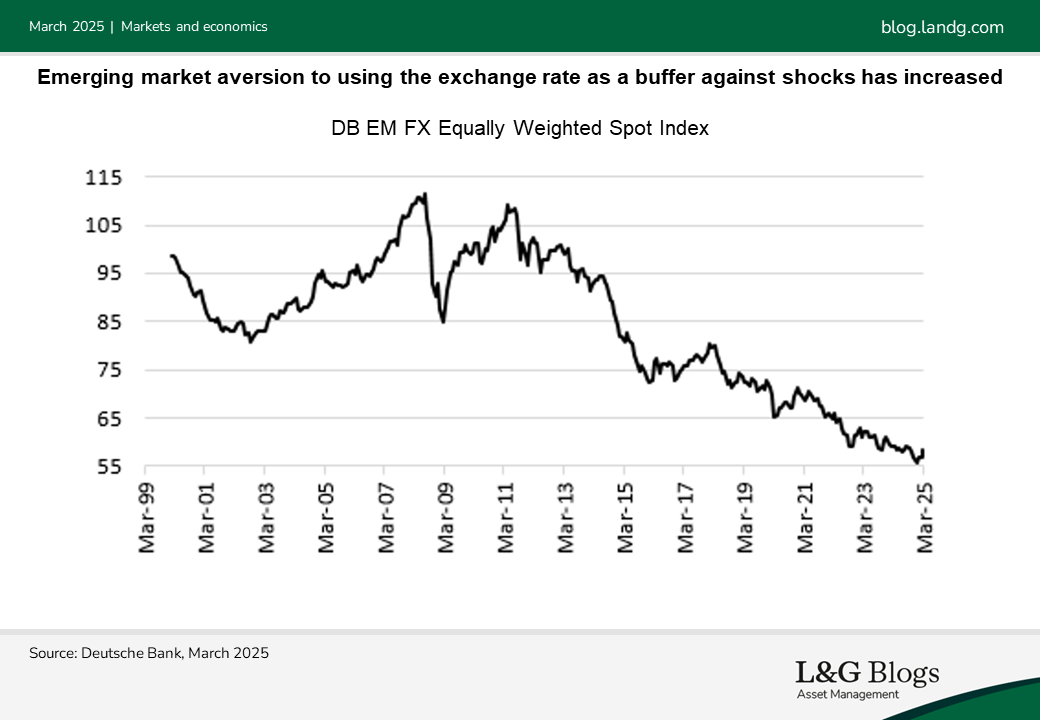

Most of the countries with heavy remittance exposure are rated either investment grade or high BB, implying stronger buffers via FX reserves, large local markets, more flexible exchange rates and access to global capital markets. EM local markets – catering to both sovereign and corporate issuers – were sized at nearly $25 trillion at the end 2024, having doubled since 2014[2]. This growth in local markets is testimony to reforms carried out over the last two decades, with many emerging markets moving to more credible monetary policy and exchange rate frameworks.

Further, relatively contained EM spreads means market access remains strong for emerging markets experiencing larger needs.

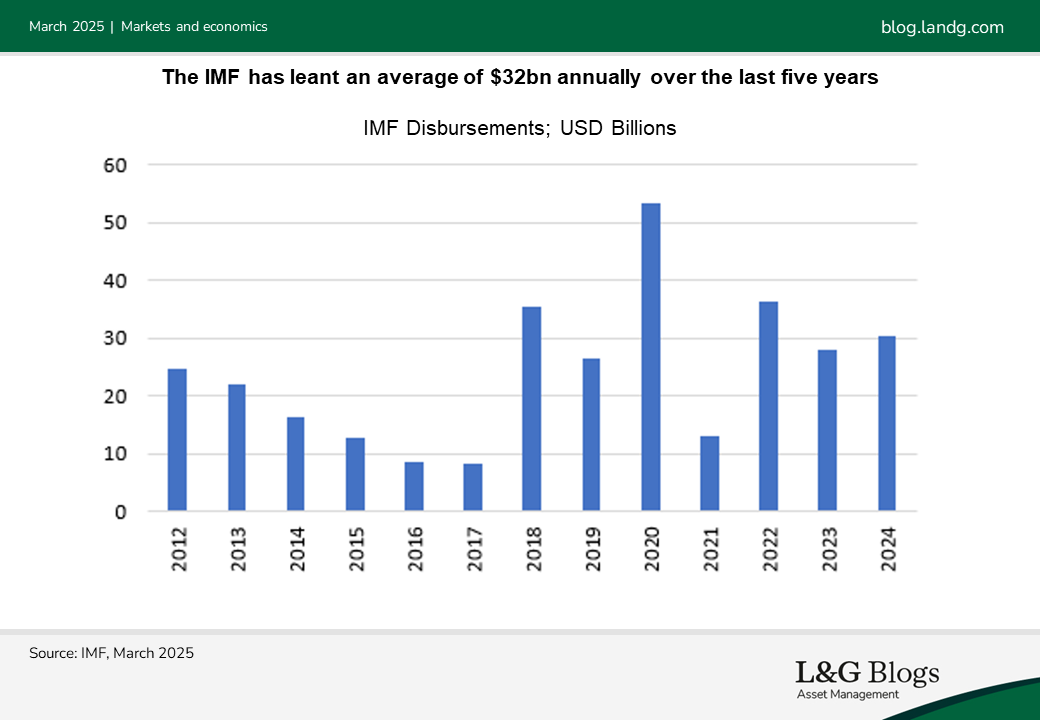

Indeed, despite the uncertainties around the US macro and policy outlook, issuance from EM sovereigns in the year to date – $82.5 billion – is running close to record levels[3]. Meanwhile, lower-rated credits such as Honduras and El Salvador are benefiting from ongoing IMF programmes that could help facilitate greater financial support if need be. Indeed, the post-Covid period has seen multilateral agencies increase their support for emerging markets.

Concluding thoughts

Rapid changes in US policies pose risks for emerging markets. However, the EM world is much stronger than it used to be. Nowhere is this more evident than in Asia, home to some of the world’s fastest growing economies. Reforms since the Asian Financial Crisis in 1997 have opened the door to decades of growth outperformance, with Asian countries continuing to anchor EM growth, FX reserves and ratings. This story is not only about China and India – Indonesia, Philippines, Malaysia, Vietnam are all examples of how countries can turn the corner.

Assumptions, opinions, and estimates are provided for illustrative purposes only. There is no guarantee that any forecasts made will come to pass. Past performance is not a guide to the future.

[1] Source: foreignassistance.gov, 2025

[2] Source: JP Morgan, IMF, L&G calculations, March 2025

[3] Source: Morgan Stanley at at 14 March 2025

Recommended content for you

Learn more about our business

We are one of the world's largest asset managers, with capabilities across asset classes to meet our clients' objectives and a longstanding commitment to responsible investing.