Disclaimer: Views in this blog do not promote, and are not directly connected to any L&G product or service. Views are from a range of L&G investment professionals, may be specific to an author’s particular investment region or desk, and do not necessarily reflect the views of L&G. For investment professionals only.

Prepare, don’t predict: a timeless playbook for geopolitical risk management

Geopolitical events can be especially challenging for investors. They are often emotive, highly uncertain, and prone to hyperbole in headlines – all factors that can lead to poor decisions. To impose discipline, the Asset Allocation team follows a 10-point guide for managing geopolitical risk that embodies the ‘prepare, don’t predict ethos.’

This framework helps us assess, monitor and respond to geopolitical threats in a consistent, level-headed way and is designed as a timeless guide that investors can revisit as new scenarios arise.

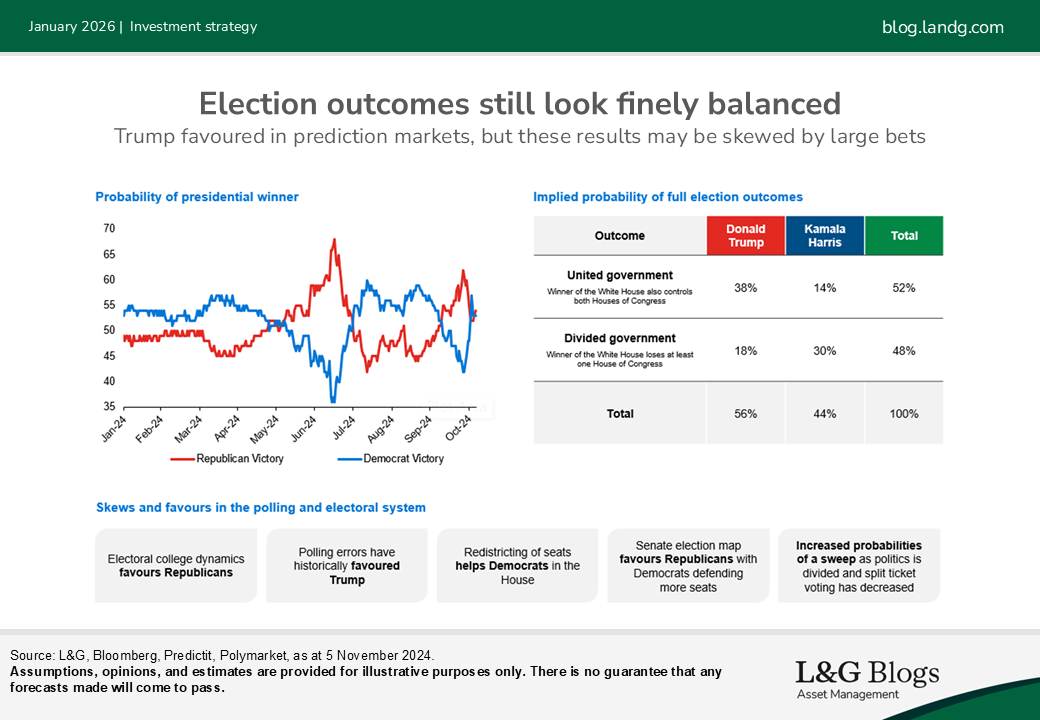

1. Acknowledge behavioural biases. Geopolitical crises provide fertile ground for behavioural biases to wreak havoc on decision-making. When shocking headlines and alarming images dominate the news, even seasoned investors can feel compelled to do something – often not out of strategy, but out of fear or external pressure. We must recognise this human tendency. Journalists and editors know that ‘bad news sells’. Studies show roughly half of all reported news is negative, and only a tiny fraction positive, which can induce biases like overestimating the probability of rare events because they’re vividly portrayed in the news. That problem is particularly acute when it comes to financial news reporting. Herding behaviour is also common – if others are selling in panic, we feel the urge to follow. Our mantra here is to be aware of these biases and counteract them with process. The below chart gives an example from 2024:

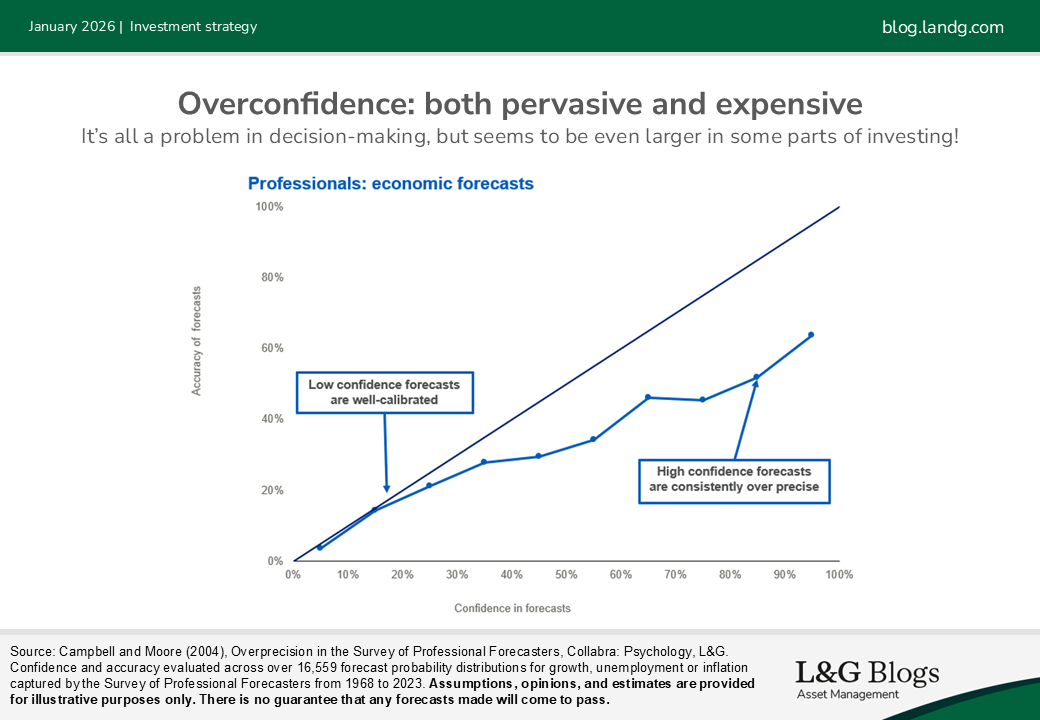

2. Understand the pitfalls of forecasting. Geopolitics is notoriously hard to forecast – and macroeconomic forecasting isn’t much better. It’s sobering to note that even professional economists have a poor track record at predictions. One extensive study of 16,000+ economic forecasts since the 1960s found that, on average, experts who claimed ~50% confidence in their predictions were correct only about 20% of the time.[1] Their confidence far outstripped accuracy. We take these findings to heart: we do not place faith in precise forecasts – our own or anyone else’s. Whether it’s trying to call election results, or conflict outcomes, we treat specific predictions with deep scepticism. In fact, an important part of our strategy is sometimes to exploit others’ overconfidence: if market prices reflect an overly confident forecast, we may take the opposite side, knowing that when reality surprises, the overconfident consensus will have to rapidly readjust – and that can create opportunity for the prepared.

3. Beware the experts. Related to the above, it’s important to put expert opinions in context. Subject-matter experts – say, a regional political expert or an economist who’s spent 30 years studying inflation – undoubtedly have deep knowledge. But experts can struggle to translate their knowledge into accurate, contextualised probabilistic forecasts. In fact, studies comparing domain experts to generalist ‘superforecasters’ show that experts often over-predict the likelihood of dramatic outcomes, reflecting a tendency to overweight their niche concerns. We guard against this by blending expert input with broader perspective. Finally, beware of pundits who have incentives to be extreme – often, the boldest, most categorical predictions get the most airtime, but that doesn’t make them the most likely. We’d rather listen to the person who says, “I’m 60%/40% on two scenarios” than the one who insists “I guarantee this will happen”.

4. Monitor geopolitical risks systematically. Rather than vaguely stating ‘geopolitical risk feels high right now’, we try to quantify and track geopolitical risk with data. Fortunately, extensive academic and industry research has given us tools to do this. For example, the Federal Reserve has a news-based Geopolitical Risk (GPR) Index that scans newspapers for geopolitical terms – it can tell us, in effect, how unusual the current level of geopolitical news flow is compared to history. Similarly, surveys, investor polls and market measures of volatility quantify risks. When monitored together, we can contextualise the risk level and seek contrarian opportunities. Historically, when geopolitical risk indices spike to extreme highs (during wars or crises), it has often been a contrarian buy signal for markets. Overall, systematic monitoring keeps us evidence-based rather than gut-driven in assessing geopolitical risk.

5. Use forward-looking monitors. When a specific geopolitical event is on the calendar – an election, a referendum, a policy deadline – we follow a structured approach to gauge the odds and potential outcomes. In our experience, polls and expert surveys provide a starting point, but betting and prediction markets tend to be more reliable. They assimilate information quicker, and more quantitatively. And we update as new data emerges. This forward-looking, probabilistic mindset helps avoid surprises – if something other than the base case happens, we’ve already thought it through.

6. Conduct scenario analysis. This is the heart of ‘prepare, don’t predict’. For major geopolitical risks on the horizon (or sudden shock that erupts), we map out multiple scenarios and their potential market impacts in advance. It’s akin to a playbook for each scenario. We assign probabilities to each and then write down what we think would happen in equity, bond and currency markets in each case. Crucially, we also identify signposts that might signal which scenario is unfolding. This way, we can update our scenario likelihoods (rather than stubbornly sticking to our initial guess). By the time the event arrives, we have a roadmap of actions ready. Scenario analysis forces us to consider outcomes ahead of time, so that if they occur, we’re responding according to a plan, not reacting in panic. This approach paid off, for example, during events like Brexit and the previous US elections – even though our base cases were wrong, we had investment plans in place for the surprise outcomes.

7. Align actions with the proper time horizon. Geopolitical events often create short-term market noise that can obscure the long-term signal. As many of our clients have long-term objectives, we constantly remind ourselves not to let short-term turbulence derail long-term strategy. This principle often means two things: staying invested and staying patient. First, we design portfolios so that they can ride out volatility without forced selling. Second, we choose our battles: most of the time, it’s better to keep a strategic, long-term position than to trade around every political headline. Repeatedly jumping in and out can whipsaw performance and incur costs. A study of investor behaviour shows that those who trade frequently in response to news tend to underperform those who stick to a disciplined plan.[2] Focus on the horizon. Many geopolitical flare-ups (even serious ones) have surprisingly short-lived market impacts.

8. Track the transmission. Not all geopolitical risks are equal for markets. A crucial step is to distinguish between noise and truly fundamental impacts. We ask: How, specifically, could this event affect economies or corporate earnings or default risks? We trace the transmission mechanisms. For example, a regional conflict might be tragic, but if the countries involved make up a small share of global GDP and trade, the direct impact on global growth could be minor. A contentious election might generate headline rhetoric, but what matters is whether policy actually changes in a way that affects corporate cash flows or investor behaviour. We try to quantify these things: e.g., “If policy X happens, it could shave 5% off next year’s S&P 500 earnings”, or “If trade tensions cut 0.5% off global GDP, historically that might pull down yields by Y basis points and equities by Z%.” By sizing the impact, we can judge if the market reaction is overdone or under-reflecting a risk. Understanding magnitude helps avoid overreacting to events that are emotionally significant but financially small.

9. Decide: hedge or harvest. If the evidence that forecasting is difficult and acting can be costly is still not enough, and you are compelled to act, an investor has a fundamental choice: try to hedge the risk, or to lean in and earn a potential risk premium for bearing it. The natural instinct is often to hedge – to reduce exposure to anything that might be impacted, seek safe-havens, or buy protection. Hedging is easy, feels good, and can be prudent, especially if a portfolio has outsized exposure to a looming risk. However, we caution against reflexive hedging of every geopolitical risk. Why? There are trade-offs:

- Hedging usually has a cost – either an explicit cost or an opportunity cost

- If done late, hedging can lock in losses (selling after a selloff) or be very expensive when fear is already priced in.

- Chronically hedging will diminish long-term returns, since investors are generally rewarded for bearing risk over time.

Given these, our approach is nuanced: we hedge selectively and efficiently – and often we choose to instead ‘harvest’ the risk premium by maintaining or even adding exposure when others are panicking – essentially providing insurance to others and potentially collecting the premium if the worst doesn’t happen. That said, this is done carefully. A disciplined, repeated engagement with diverse geopolitical risks can be a source of alpha. The key is to size positions modestly and diversely on the rationale that not all fears will materialise. Over time, if we’re right more often than not (or if markets over-price these risks systematically), the strategy could earn a premium.

10. Diversification remains the best defence. Finally, the most enduring principle in risk management: don’t put all your eggs in one basket. For geopolitical risk, this is absolutely crucial. By maintaining a well-diversified portfolio across asset classes, regions and risk factors, we increase the likelihood that when a given geopolitical shock hits one part of the portfolio, other parts may hold steady or even benefit. We also stress liquidity as part of diversification: in uncertain times, holding some assets that can be quickly rebalanced is invaluable, and being able to provide liquidity to stressed markets can generate outsized returns.

By following these guidelines, we ensure that we respond thoughtfully and strategically, rather than react impulsively. Crucially, this approach turns geopolitical risk management into a repeatable process – one that we can apply over and over as new crises emerge, without having to reinvent our playbook each time.

In case you missed the first blog in this series, we explored why uncertainty isn't the enemy in portfolio preparation. Next, we provide a timely case study of how the mindset and principles described above apply to a real-world scenario, demonstrating the ‘prepare, don’t predict’ philosophy in action.

Assumptions, opinions, and estimates are provided for illustrative purposes only. There is no guarantee that any forecasts made will come to pass. It should be noted that diversification is no guarantee against a loss in a declining market.

[1] Overprecision in the Survey of Professional Forecasters, Campbell & Moore, 2024

[2] Trading Is Hazardous to Your Wealth, Barber and Odean (2000), Journal of Finance

Recommended content for you

Learn more about our business

We are one of the world's largest asset managers, with capabilities across asset classes to meet our clients' objectives and a longstanding commitment to responsible investing.