Disclaimer: Views in this blog do not promote, and are not directly connected to any L&G product or service. Views are from a range of L&G investment professionals, may be specific to an author’s particular investment region or desk, and do not necessarily reflect the views of L&G. For investment professionals only.

Margin call: will ‘middlemen’ markups amplify tariff inflation?

Does the behaviour of branded baked-bean prices during the energy crisis point to upside risks to tariff inflation from ‘middlemen’ markups?

While nobody knows where President Trump’s tariffs will ultimately settle, I worry that we’ll end up with a repeat of the energy crisis, with inflation surprising to the upside for a given level of tariffs. Firms could amplify the tariff bill if they once again set prices as a specific multiple of costs.

Beanz no longer meanz Heinz

There are few branded items in my food cupboard these days. I was surprised and upset by how much branded goods went up relative to unbranded ones during the energy crisis (especially chocolate hobnobs!)

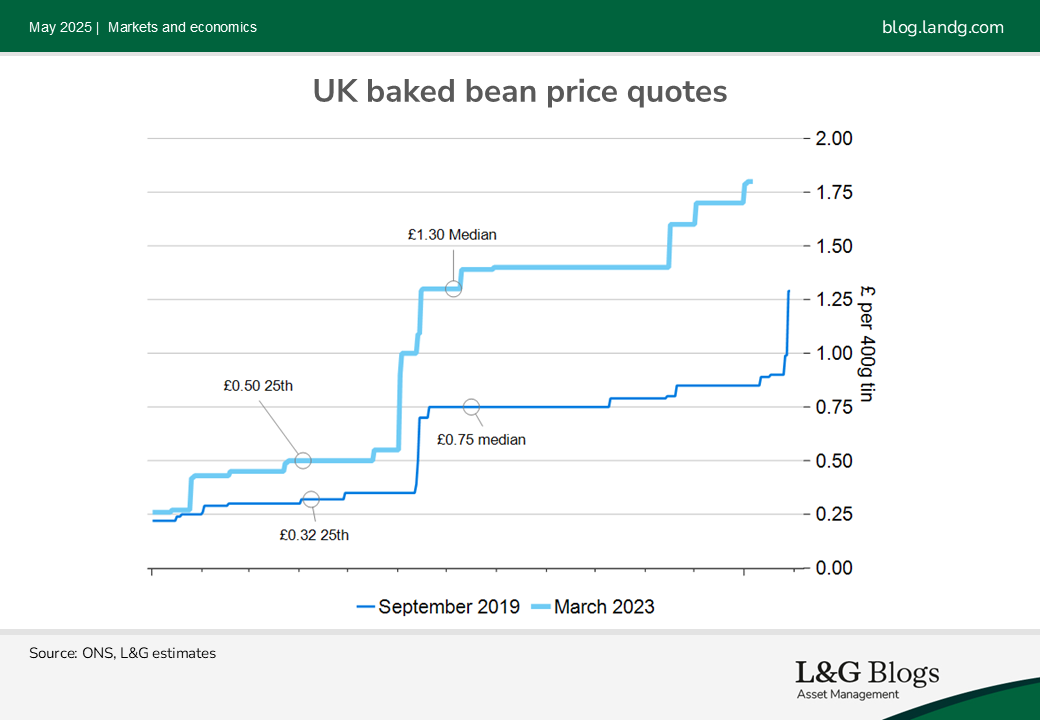

After all, a greater share of unbranded items’ costs should be energy, transport and raw materials. Advertising bills didn’t rise with energy. Yet the median (branded) price of baked beans rose by 55p versus 18p for the 25th percentile (shops’ own brand). The ratio of branded to non-branded actually increased.[1] They’re tastier, but not that much tastier!

Branded baked bean prices rose by more than own brand, despite having a greater share of marketing costs.

Markups explained

This was attributed to firms trying to maintain percentage rather than dollar markups. What does that mean? Well let’s take the example of the classic lemonade stall.

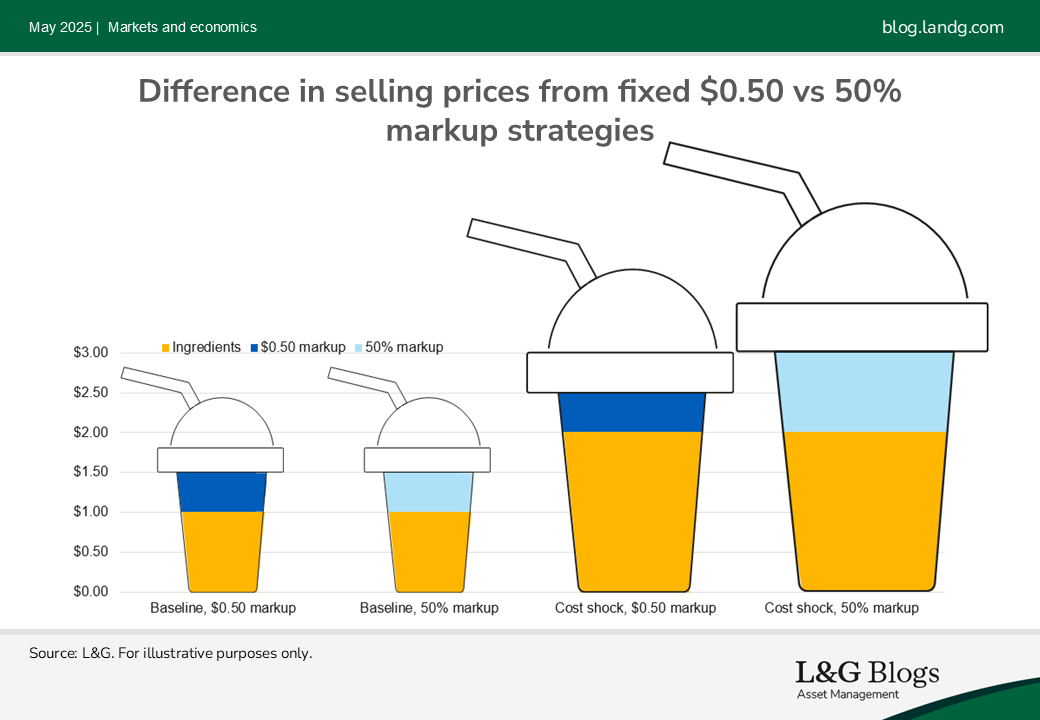

Let’s assume the cost of lemons, sugar, water and paper cups are $1, but I sell the drink for $1.50. The markup is $0.50 in absolute terms, or 50% in percentage terms ($0.50 markup over a $1 cost base).

Now let’s assume a bad harvest raises the price of lemons such that my ingredients now cost $2; an increase of $1 from before. What do I do with my sale prices? Well in theory, the cost of my labour hasn’t gone up. So I should charge $2.50, right? An unchanged $0.50 markup over my new costs.

Or do I continue to charge a 50% markup over my costs? After all, the cost of my lemon inventory has gone up. If I don’t sell them and they rot, I lose more money than before. Greater risk, greater reward. So I should continue to charge a 50% markup over the new $2 cost base, pushing my selling price up from $2 to $3.

As you can see, whether I set my markups in fixed dollar or proportional percentage terms has huge ramifications for sale prices.

A $1 cost shock leads to a $1 increase in sale prices if my markups remain unchanged in dollar terms. Or it can be amplified to a $1.50 increase in sale prices if I maintain the 50% markup.

% markups can amplify the impact of a given cost shock

What happens in the real world? In a recent paper, the founder of Pricestats (which tracks daily retail prices) – Professor Alberto Carollo – found stable percentage total markups (retail prices over manufacturing costs) for a major consumer-staples company from 2018-23. He matched data for costs, wholesale and retail prices across 1,900 products, 13 brands, seven categories and four countries. This suggests companies amplify cost shocks through their pricing strategies.

Tariff multipliers

What could this mean for tariffs? Let’s take the typical breakdown of a pair of Nike trainers. Of the $76 average selling price, only $22 (~30%) is the manufacturing cost. Assuming they’re imported, a 10% tariff should therefore raise prices by just $2.20. However, the energy crisis suggests they could go up by $7.60 if all percentage markups remain the same.

The more ‘middlemen’ in the chain, the greater the problem. Carollo finds retailers have a 35% markup. So, per $100k of tariffs on ‘finished goods’ (e.g. trainers), prices could go up by $135k.

By contrast, if a US manufacturer pays $100k of tariffs on intermediate goods (e.g. leather), not only could they raise wholesale prices by their typical 2.2x markup relative to costs ($220k), but the retailer might then add on their 35% markup, boosting the total bill to $300k.

Overall, we estimate a multiplier of 1.5x the tariff cost; taking into account the split of finished, intermediate and capital goods (which we assume have a slow passthrough).

Two-way caveats

Our research could be too pessimistic on inflation. The consumer-staples industry might not be representative, as it could have high pricing power given it sells low-cost items. The macro period was also exceptional, with fiscal support during the covid and energy crises. Foreign companies might also cut prices somewhat given the negative demand shock from US tariffs. Multinationals could also spread price rises globally to avoid undue political attention.

Offsetting this is the price response from domestic manufacturers. Cavallo shows US-made products in tariff-affected industries are already raising prices in tandem with imported ones. We saw this with washing machines in 2018, where US Whirlpool and Maytag brands rose prices in tandem with tariffed LG and Samsung ones.

Moreover multiple papers show that larger and ‘common’ shocks are passed on more aggressively (both magnitude and pace).

Overall, we’re watching the pricing decisions of firms closely. Our analysis supports the Fed’s cautious approach to monetary policy, particularly if fiscal policy is loosened, which would further support firms’ pricing power.

Assumptions, opinions, and estimates are provided for illustrative purposes only. There is no guarantee that any forecasts made will come to pass. *For illustrative purposes only. Reference to a particular security is on a historic basis and does not mean that the security is currently held or will be held within an L&G portfolio. The above information does not constitute a recommendation to buy or sell any security.

[1] Cavallo finds cheaper items rose by slightly more in percentage terms than more expensive items during the energy crisis. But given the spread of starting prices, this still implies a greater dollar increase in price for branded items despite marketing costs unchanged.

Recommended content for you

Learn more about our business

We are one of the world's largest asset managers, with capabilities across asset classes to meet our clients' objectives and a longstanding commitment to responsible investing.