Disclaimer: Views in this blog do not promote, and are not directly connected to any L&G product or service. Views are from a range of L&G investment professionals, may be specific to an author’s particular investment region or desk, and do not necessarily reflect the views of L&G. For investment professionals only.

The Bank of England and the gilt market: more is less, more or less

The fate of government bond markets is intertwined with the actions of central banks. In the post-COVID economy, central banks around the world have been buying large quantities of government bonds to improve market functioning, and ultimately boost economic activity and inflation.

Relative to international peers, the Bank of England (BoE) arrived a little late to the party. The European Central Bank expanded its asset purchase programme on 12 March. On the same day, the Federal Reserve restarted purchases of US Treasuries. The Bank of England waited until 19 March before announcing a similar programme.

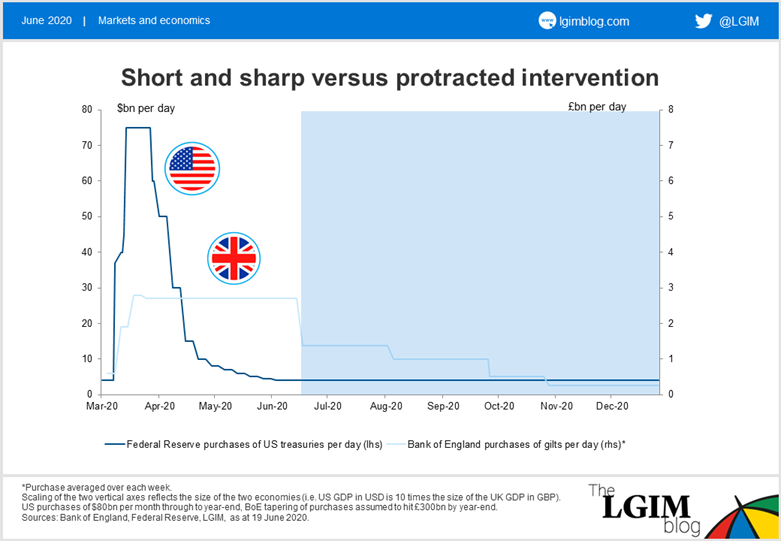

However, having arrived late, the BoE stayed longer. Since mid-March, the BoE has been buying £13.5 billion of gilts – week in, week out. That is in stark contrast to the Federal Reserve, where an initial splurge to restore confidence has been followed by a steady tapering. On an annualised basis, £13.5 billion is equivalent to just over 30% of Britain’s pre-crisis GDP. This pace was clearly unsustainable for any prolonged period of time. The BoE risked overstaying its welcome unless it evolved its strategy.

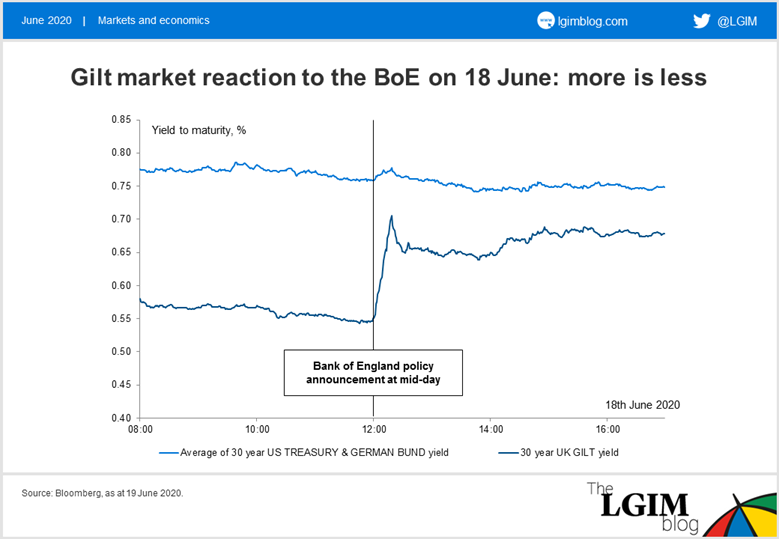

At its recent policy meeting, the Bank’s Monetary Policy Committee decided to expand the overall “envelope” of asset purchases by £100 billion. The Committee described this as a “further easing of monetary policy”. The BoE insists that the total stock of purchases is what matters for the stance of monetary policy. The Bank is increasing the target stock from £645 billion to £745 billion, so considers itself to be doing more.

But gilt prices (and therefore yields) are determined by the interaction between buyers and sellers on a daily basis. From the market’s perspective, it is the flow of purchases that determines how much of the record-busting issuance needs to be borne by private sector buyers. As that proportion rises, the compensation demanded by investors to absorb that risk increases. Prices are set at the margin. As the BoE steps away, the gilt market will have to draw in more marginal buyers.

The flow of BoE purchases is set to drop from £13.5 billion per week to £7 billion per week in the near term, and dwindle to nothing by the end of the year. The BoE may insist that it is doing more in stock, but the gilt market sees it as doing less in flow. You can see that in the kneejerk reaction to the announcement, with long-dated gilt yields jumping 10 basis points higher on a day when yields in other markets were falling.

This implies that investors will have to pay much more attention to fiscal policy risks in future. The Debt Management Office pronouncements on issuance have previously been treated with a collective shrug of the shoulders and an assumption that the BoE would simply hoover up all the additional bonds. No longer.

The BoE’s backstop of the gilt market is still there in extreme circumstances (such as a second wave of the virus which triggers another bout of market dysfunction), but the gilt market will have to stand on its own feet in the months ahead. More or less.

Recommended content for you

Learn more about our business

We are one of the world's largest asset managers, with capabilities across asset classes to meet our clients' objectives and a longstanding commitment to responsible investing.