Disclaimer: Views in this blog do not promote, and are not directly connected to any L&G product or service. Views are from a range of L&G investment professionals, may be specific to an author’s particular investment region or desk, and do not necessarily reflect the views of L&G. For investment professionals only.

What happens when the market loses its anchor?

How fading US exceptionalism may mean short-term uncertainty but long-term benefits for emerging market equities.

The US might still be the most prosperous market in the world, but the exceptionalism many commentators attached to its economy appears to be waning.

Since ‘Liberation Day’, new tariff policies and a recession scare have generated volatility in US risk assets. Indeed, in the long history of American capital markets, it is rare to see equities, credit, and the US dollar all decline at the same time.

At the time of writing, it appears that investors are still sitting on the sidelines and hesitating to sell US assets. After all, many investors still view the US as the most attractive market in the world, underpinned by free markets, high levels of innovation, the rule of law, and a democratic system.

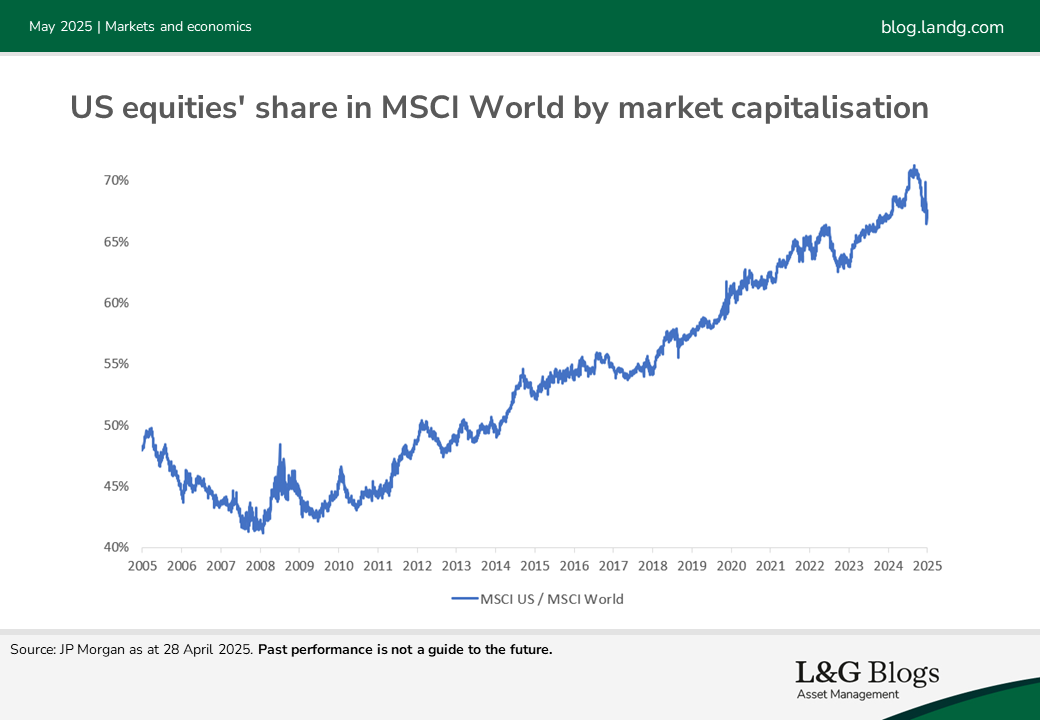

However, after more than a decade of outsized focus on the US, we believe investors could eventually start to look elsewhere. Despite this year’s falls, American assets are over-owned: their share of MSCI World is currently over 70%, compared to under 50% 15 years ago[1]. Admittedly, the country’s recent economic strength is largely a consequence of fiscal and monetary expansion since the pandemic, which cannot continue forever. Recession concerns might be cyclical, but structural issues such as a dollar oversupply and mounting government debt are more difficult to overcome.

The US administration is prioritising the restoration of competitiveness in US manufacturing, for which a weaker dollar may be necessary. The US dollar is also being challenged by its oversupply and increasing concerns over the greenback’s safe-haven status. In a recent note, Oaktree Capital’s co-founder Howard Marks suggested that the US government's spending pattern was similar to owning a “golden credit card with no credit limit”[2]. But what if there is a credit limit – and the bill finally arrives this time?

Will a weaker dollar benefit emerging markets?

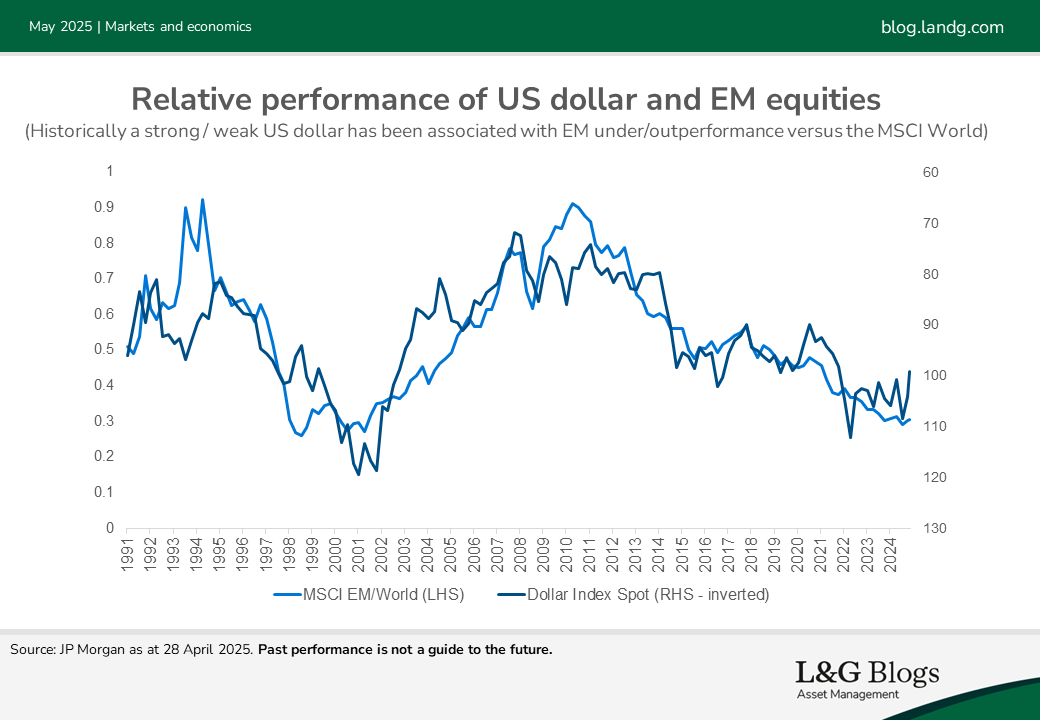

Emerging market (EM) equities have historically tended to benefit from a weaker dollar; a weaker dollar has typically led to lower dollar returns and improved global liquidity, which in turn encouraged inflows into non-US investments. More importantly, a weaker dollar has also often corresponded with a compression in global risk premia: i.e. investors become ‘risk-on’ and sought higher-beta opportunities.

A key argument for EM equities is global investors’ low allocations and a widened valuation gap compared to US equities after a continuous 15-year derating. If the logic of mean reversion applies, EM equities could potentially start to outperform amid a weakening dollar outlook. However, despite the overall positive context for EM, there are reasons the conventional wisdom might not apply this time.

First, the global risk premium remains elevated. Global investors appear extremely risk averse due to a highly uncertain situation around US tariffs and macroeconomic trajectory. Growth appetite is muted with little ‘risk-on’ sentiment. Instead of diversifying into EM equities in a typical weaker dollar scenario, investors have fled into the perceived safety of assets such as gold.

Indeed, although EM equities have outperformed year-to-date, the degree of this outperformance is low compared to historical periods of US dollar weakness. The traditional relationship has been closer to EMs gaining two points for every one point percentage point decline in the DXY, and vice versa) according to analysis done by JP Morgan[3].

Second, traditional wisdom in EM risk assessment and valuation could be challenged by fast deteriorating confidence in US assets. Investors could immediately struggle to calculate the appropriate cost of capital for EM equities if the US 10-year treasury yield is no longer the risk-free anchor.

In a scenario of elevated 10-year treasury yields, what would happen to corporate credit spreads? Would the historical correlation to US assets still be valid? If the anchor is lost, the rest of the world could find it hard to locate themselves.

A silver lining for emerging markets?

Although EM equities might not be clear-cut beneficiaries of waning US exceptionalism, we still see both near-term and long-term opportunities for them.

In the near term, we believe many EM governments and central banks have the capacity to adopt proactive fiscal and monetary policies to drive economic expansion. EM countries have lagged developed markets (DM) in fiscal stimulus since COVID-19 and their prudent stances may be reversed. EM central banks also appear more dovish in rate cuts than the US Federal Reserve, as inflation has softened and growth has become a bigger concern. A weaker dollar may also be accommodative for more EM rate cuts.

Over the long term, we believe the ongoing changes in the global market structure and world order could create new opportunities for EM. For investors willing to look at the long term, therefore, any short-term uncertainty may potentially create attractive entry opportunities.

First, if the global trade surplus against the US shrinks, capital flows into the US could dry up. In other words, more capital would stay in non-US markets – even in the face of global risk events. It’s possible that non-US equities would no longer behave like the typical high beta assets or victims of capital flight.

Second, if the global economy does enter a new era of deglobalisation, all countries in the world will need to re-assess and adapt their strategies. The question is: how will EMs position themselves in the emerging new world order? Previously, many EM countries suffered from high levels of leverage and low productivity. These issues might persist, but deregulation, AI proliferation and heightened focus on domestic markets could create opportunities to grow productivity.

Finally, while free trade may have had unintended consequences for American national security, US corporates have benefitted from globalisation. They managed to outsource the capital-intensive parts of their supply chains to EMs while still capturing the lion's share of profits thanks to their strong intellectual property and superior brand power.

This partially resulted in the widening return of equity (ROE) gap between US and EM equities: while the ROE of EM companies was stagnant, the ROE of corporate America was constantly on the rise. Reshoring manufacturing back to the US might make strategic sense, but could be counterproductive in economic terms. Productivity could reduce, leading to ROE erosion.

We might therefore eventually start to see the narrowing of valuation discounts of EM equities versus the US, driven by a shift in relative ROEs.

[1] Source: Bloomberg as at 29 April 2025

[2] https://www.oaktreecapital.com/insights/memo/nobody-knows-yet-again

[3] Source: JP Morgan as at 28 April 2025

Recommended content for you

Learn more about our business

We are one of the world's largest asset managers, with capabilities across asset classes to meet our clients' objectives and a longstanding commitment to responsible investing.