Disclaimer: Views in this blog do not promote, and are not directly connected to any L&G product or service. Views are from a range of L&G investment professionals, may be specific to an author’s particular investment region or desk, and do not necessarily reflect the views of L&G. For investment professionals only.

When small parcels mean big business

For all the noise on headline tariff rates, tariffs on small packages are underdiscussed.

The impact from great crises, conflicts between nations and radical technological change, can easily remind us how small we are in the face of world events.

But sometimes, changes in smaller arenas can also produce profound change. The Eurodollar market’s concentration in London is owed largely to a minor ruling from a regulator back in 1955. An unnoticed exemption of the postal savings system from Japan’s 1997 banking reforms has helped fund the country’s enormous debt burden accrued since.

Similarly, recent months have seen clashes over trade and tariffs, but one lesser-known change was also made. Amid the fireworks accompanying the launch of tariffs on China over the trade in fentanyl, the US closed the arcane ‘de minimis’ exemption for Chinese imports. Moreover, while many of the tariffs between the US and China have been unwound, this has not.

In this piece I’ll explore the de minimis exemption, and what its closure means for trade policy and the wider economy.

Small threshold, big freedom

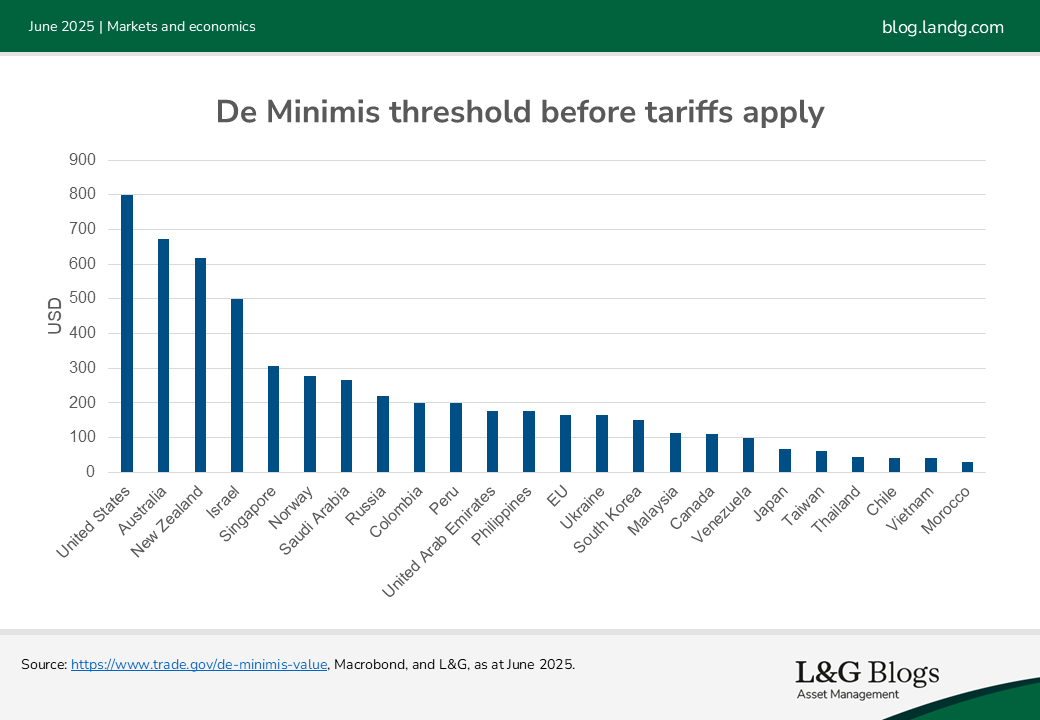

The de minimis threshold essentially sets a floor below which the government cannot tax imports. Just as it’s not worth driving 800 miles to get five cents extra on bottle returns, the government isn’t going to chase people for taxes due on trivial purchases. This floor exists everywhere, but despite its hawkish turn in trade policy, the US continues to maintain the highest de minimis floor among major countries. Consequently, that leaves a big door open to largely Chinese imports via online retailers such as Shein and Temu.

The exemption has fueled the growth of e-commerce trade, with the total volume of packages labelled under the US scheme growing to 1.36 billion in 2024, up from 255 million in 2016. The total value of these de minimis imports was ~$65bn last year, a small (just 2%) share of goods imports, but that share has doubled since 2016, and has outsized effects on household consumption.

Tariffs on China, first imposed under President Trump in 2018, have incentivised this growth further, as importers restructured trade to get larger volumes in under the scheme, often using third countries. There is also concern that illicit goods, such as drugs and counterfeit items, are admitted to the US using this rule.

With the Trump administration back in power, they see closing the de minimis rule as essential to halt tariff circumvention, illegal trade and to wring much-needed revenue.

Not worth the candle?

But despite the earnest intentions of policymakers, closing the rule is likely to come with considerable losses. Risks come from three major sources.

First, it isn’t clear the US can actively enforce closing the loophole. US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) has struggled with understaffing for some time, even before the new rules were implemented. A study found the CBP would need an additional 22,000 officials to enforce the new rule. Although new technology can help, enforcement is likely to come with at least some short-term pain.

Second, much like tariffs encouraged re-routing via third countries, closing the loophole only for Chinese products will encourage suppliers of produce (both licit and illicit) to circumvent via third countries. Ending de minimis exemptions only for Chinese-sourced packages is an open invitation for producers to circumvent their US trade.

Lastly, much like Trump’s other tariff policies, the pain will be borne by the consumer. The change could produce significant upside risk for inflation, as substantial volumes of cheap imports become liable for tariffs. Moreover, research has found that lower income households are more intensive users of the de minimis exemption, and its closure will hurt their spending power significantly. While the policy does benefit Treasury revenues, the pain will largely be borne by the low-paid.

All your parcel are belong to us[1]

The above difficulties explain why the policy was delayed by several months, and although it is on the books now, its effects on trade and domestic inflation are not well understood. The US experience may prove instructive, as both Europe and Japan are mulling similar charges, at least on Chinese goods. The small package, which once lived in a free-trade haven, is now being dragged into tariff wars along with everyone else.

Portfolio impacts

The closure of the de minimis exemption keeps US inflation biased upward, at least in the short run. For this reason, the Fed appears constrained and unable to cut rates unless it sees clear evidence of a deteriorating labour market.

[1] A perhaps niche reference to the internet meme: ‘All your base are belong to us’

Recommended content for you

Learn more about our business

We are one of the world's largest asset managers, with capabilities across asset classes to meet our clients' objectives and a longstanding commitment to responsible investing.