Disclaimer: Views in this blog do not promote, and are not directly connected to any L&G product or service. Views are from a range of L&G investment professionals, may be specific to an author’s particular investment region or desk, and do not necessarily reflect the views of L&G. For investment professionals only.

What can the London congestion charge teach us about tariffs?

Congestion charges and tariffs are very different in design, but both are attempts to use taxes to change economic behaviour. What can we learn from 20 years of the former to help guide our thinking on latter?

News dropped recently that Transport for London (TfL) is consulting on a proposal to raise the London congestion charge to £18 from January 2026 onwards.

When I heard this, my first thought was to bemoan the increase in cost. I am old enough to remember when the congestion charge was introduced in 2003 at a daily rate of just £5. Putting some structure on that, we can calculate the inflation-adjusted price change since the charge was introduced.

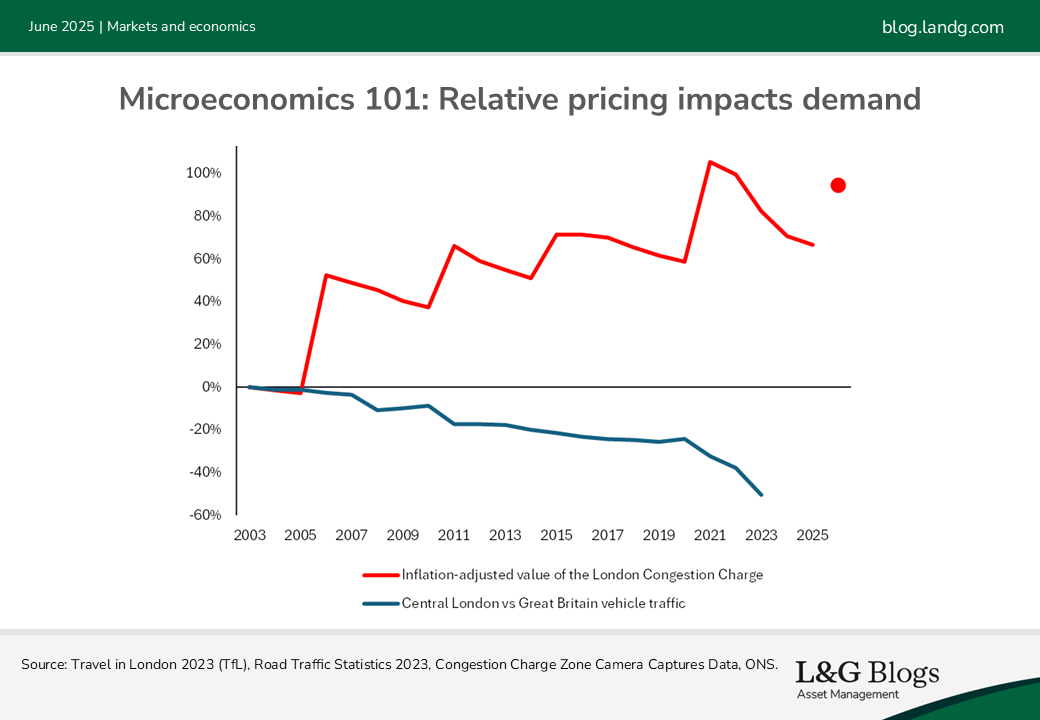

That’s the red line in the chart below. The charge is up 3.6x in nominal terms, but has ‘only’ doubled in inflation-adjusted terms since 2003. The recent proposed increase (the red dot) merely restores the inflation-adjusted price back to where it was in 2020 at the time of the last increase.

Lesson #1: Price illusion is real. The £3 increase feels like a lot but is really just catch-up for the post-COVID bout of high inflation.

My second thought, because I’m an interesting person, was “has congestion charging worked?” ‘Worked’ can mean different things to different people, but the charge certainly seems to have driven down traffic in central London. The blue line is the vehicle use in central London relative to the vehicle use across Great Britain as a whole. It has halved in the last two decades.

Lesson #2: Change the relative price and observe the change in relative demand: behold microeconomics in action!

Which got me to my third thought. Because I’m a really interesting person, this was “does this have broader implications for how we should think about tariffs?” The congestion charge is a great example of where changing the relative price has seemingly had a profound impact on relative demand, but there are so many other moving parts that it is impossible to accurately isolate the effect.

The impact on demand for a change in price is the “price elasticity of demand”. In the congestion charge’s case, initial estimates were quite low[1]. But long-run price elasticities have proven much higher with the sharp drop in demand shown in the chart above.

Lesson #3: Isolating the price elasticity of demand with any precision is impossible but it is likely to be bigger in the long run than the short run.

Applying those lessons to the recent introduction of tariffs by the US administration is potentially instructive. Tariffs will change the relative price of internationally produced goods for US consumers. If those tariffs stick, it seems reasonable to assume that they could have a profound impact on relative demand.

Estimating how big that effect will be is guesswork. The infamous equation used by the US Trade Representative to justify reciprocal tariffs assumed a “tariff elasticity of demand” of 1. That’s similar to the numbers implicit in the University of Pennsylvania’s tariff simulator. This matters because it underpins the assumption that tariffs will raise $2.5-$3 trillion in revenue for the Federal government over 10 years.

However, the congestion charge should teach us that the elasticity could be bigger in the long run than in the short run. The US government are relying on tariff revenues to offset the cost of the “One Big Beautiful Bill” that slashes taxes on households and corporates.

We are skeptical that tariff revenues can be sustained at high levels for long. A large behavioural change could trigger a larger-than 1:1 drop in import volumes. In that scenario, tariff revenues will be smaller than hoped and negative impact on foreign manufacturers will be bigger.

Lesson #4: Changes in the congestion charge have been infrequent and predictable. That has allowed drivers in central London to plan and adapt, minimising the impact of those changes.

The change in the congestion charge in 2026 will be the fifth increase since it was introduced over 20 years ago. In contrast, tariff rates applied by the US administration have changed repeatedly in the last few months. Increases in the congestion charge are flagged many months in advance whereas changes in tariffs come with a few days (and sometimes hours) notice.

Impacted business have limited scope to adjust and adapt in the face of such frequent changes.

Assumptions, opinions, and estimates are provided for illustrative purposes only. There is no guarantee that any forecasts made will come to pass.

[1] https://content.tfl.gov.uk/demand-elasticities-for-car-trips-to-central-london.pdf

Recommended content for you

Learn more about our business

We are one of the world's largest asset managers, with capabilities across asset classes to meet our clients' objectives and a longstanding commitment to responsible investing.