Disclaimer: Views in this blog do not promote, and are not directly connected to any L&G product or service. Views are from a range of L&G investment professionals, may be specific to an author’s particular investment region or desk, and do not necessarily reflect the views of L&G. For investment professionals only.

Inflation: money and the new supply-side economics

Last week, the US retail sales numbers for January smashed forecasts and once again showed that stimulus works, especially direct cash payments to households. Around 25% of the $600 received by individuals earning $75,000 or less was immediately spent, generating a $30 billion bounce in retail sales across all categories.

While this news broke, debate continued in Congress about the next round of stimulus. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen commented that “the risk of doing too little is greater than of doing too much”.

If such an approach is adopted, the direct uplift to household incomes will potentially be at least three times larger than included in the COVID-19 relief bill at the end of 2020. This money should hit people’s accounts just as the US begins to re-open more fully. Alongside the excess household savings accumulated during the pandemic, this could fuel a surge in demand.

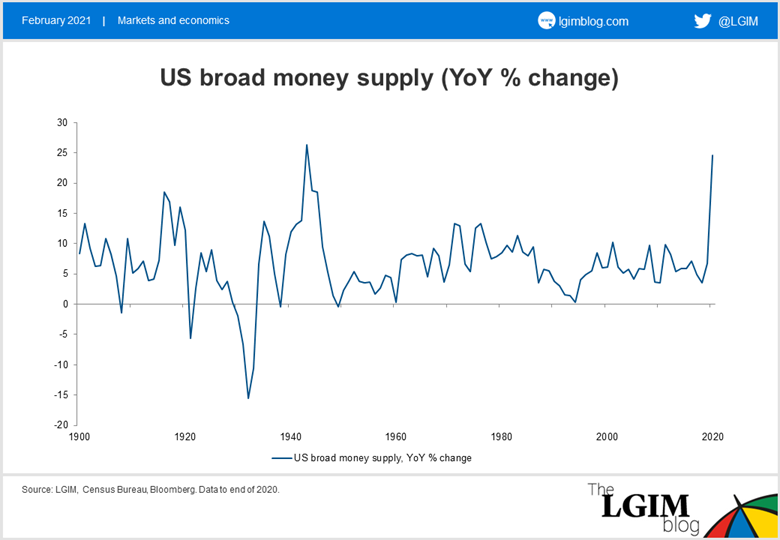

This makes us think about the implications of the money supply glut. None of us have seen money supply grow on the current scale, the only precedent being during the Second World War.

Half of the increase in broad money supply sits directly in household accounts. We believe that a significant amount of this cash will be spent rather than kept in reserve, boosting growth, corporate profitability, and possibly inflation.

All about that base effect

On inflation, we know there will be a pronounced base effect around the spring as prices fell sharply at the equivalent point of 2020 when the economy was locked down. This, plus later boosts from CPI components that were depressed by restrictions like airfares and hotel prices, could temporarily raise inflation above target-consistent levels.

The Federal Reserve has highlighted this potential outcome, with January’s meeting minutes containing a discussion on why it would be prudent to look through this increase.

This makes sense, in our view, as it is equally likely that inflation will fall back in the summer. Base effects do reverse, and there are also some aspects of inflation that have been lifted by the pandemic but are likely to weaken once the economy reopens. Used-car prices are one example.

Further out, the inflation picture becomes much murkier. How much slack will be left in the economy? Does the jump in money supply matter? Are some of the structural disinflationary forces of the past decade, like technology, beginning to shift? How well anchored are inflation expectations?

We believe that inflation becoming high enough to constrain monetary policy is still a way off. But if we get there, central banks in developed markets might be surprised by how much they have to raise rates to reduce inflationary pressure.

Why would they be surprised? First, money doesn’t play a role in their models. As former Federal Reserve Governor Larry Meyer said in 2001, “Money plays no explicit role in today’s consensus macro model, and it plays virtually no role in the conduct of monetary policy.” This is despite monetary aggregates generally being excellent predictors of some key economic metrics, particularly in the Eurozone and China.

Second, they aren’t able to directly undo the monetary and fiscal one-two that’s been so effective at putting cash in consumers’ pockets. For that, the fiscal authorities need to help them take back some of the excess. That’s not historically the strong point of a political process that operates on a short-term electoral cycle.

Recommended content for you

Learn more about our business

We are one of the world's largest asset managers, with capabilities across asset classes to meet our clients' objectives and a longstanding commitment to responsible investing.