Disclaimer: Views in this blog do not promote, and are not directly connected to any L&G product or service. Views are from a range of L&G investment professionals, may be specific to an author’s particular investment region or desk, and do not necessarily reflect the views of L&G. For investment professionals only.

Chart of the month: What can we learn from the long history of US tariff policy?

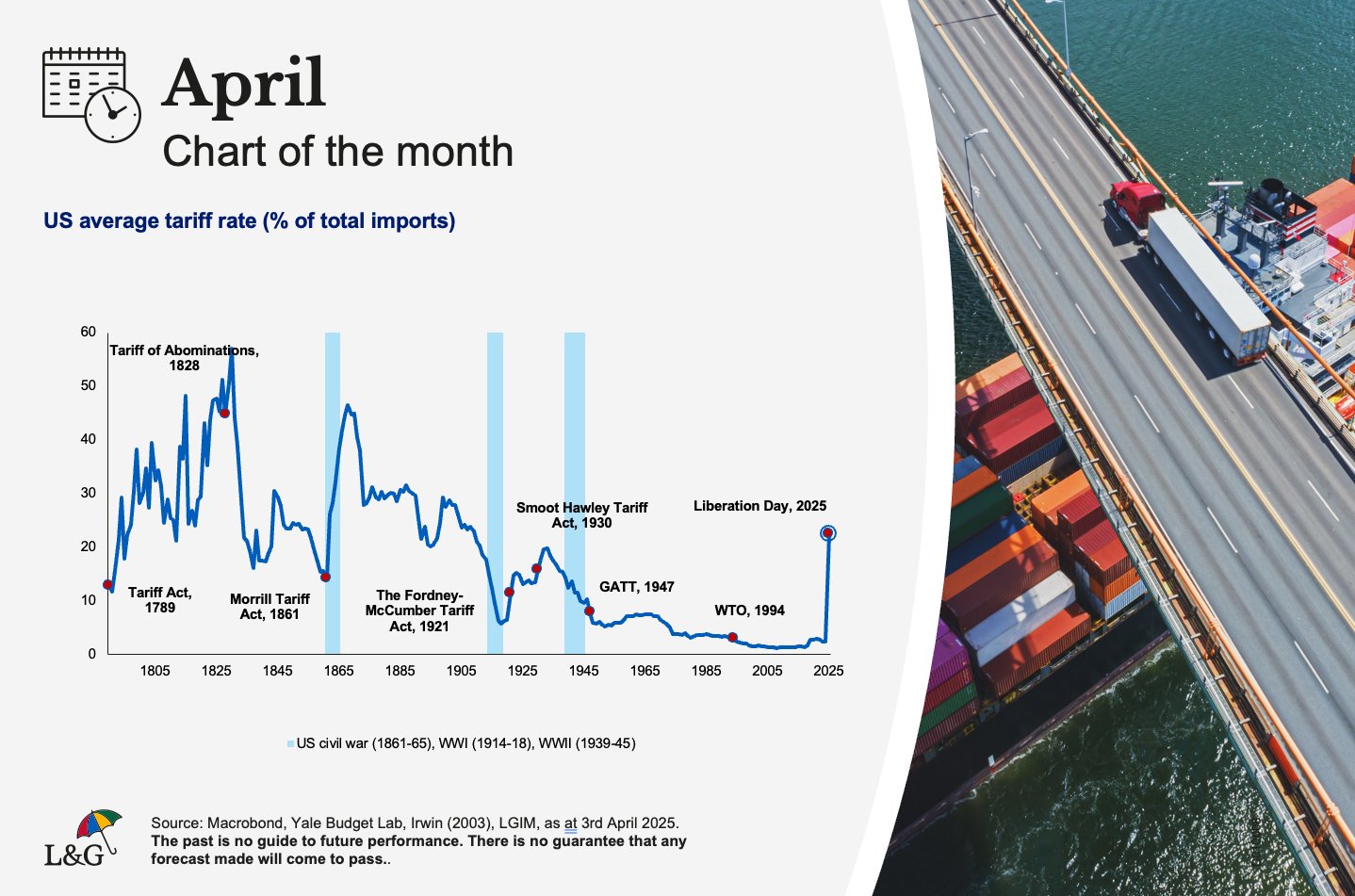

The Tariff Act was one of the first major pieces of legislation passed after the formation of the United States in 1789. Where George Washington leads, his successors have followed. Our chart of the month helps put President Trump’s tariffs in the longest possible historical context.

It is hard to know how much of the announced tariff increases will prove permanent. However, it is clear that ‘Liberation Day’ marks a sharp break from the post-war norm. Rounds of trade negotiations have seen average tariff rates fall consistently since the late 1940s. By turning back the clock, the US administration has multiple objectives: raise revenue, reindustrialise the United States, and correct the trade imbalance between the United States and the rest of the world. So, how likely are they to achieve those goals?

Tariff increases on the scale just announced have few historical precedents. We have to go back nearly 100 years to the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930 to get close. History has not been kind to Reed Smooth and Willis Hawley’s legislation. It was designed to “encourage the industries of the United States” and to “protect American labor”. In fact, it did the opposite. Rather than a dry retelling of economic history, we can instead turn to the immortal words of Ferris Bueller’s Day Off:

“In 1930, the Republican-controlled House of Representatives, in an effort to alleviate the effects of the... Anyone? Anyone?... the Great Depression, passed the... Anyone? Anyone? The tariff bill? The Hawley-Smoot Tariff Act? Which, anyone? Raised or lowered?... raised tariffs, in an effort to collect more revenue for the federal government. Did it work? Anyone? Anyone know the effects? It did not work, and the United States sank deeper into the Great Depression.“

Going even further into the past, previous bouts of sharp tariff increases have been more successful at raising revenues. The original Tariff Act of 1789 provided the bedrock of Federal revenue. The Morrill Tariff Act in 1861 was instrumental in funding the Federal government through the Civil War. Unfortunately for the current administration, the Federal government is a lot bigger than in the 1780s or 1860s. According to the Congressional Research Service, 90% of Federal Revenue prior to the war of 1812 was from customs duties (i.e. tariffs). That figure was still 50% between the US civil war and WW1. But in the last two decades, tariffs have provided less than 1.5% of revenue.

The history lesson is helpful in highlighting the tension at the heart of the tariff policy. High tariff rates could potentially be successful at driving down imports and partially reindustrialising the USA, but then tariff revenues would be likely to be disappointing. Or they can generate high revenues for the government, but only if import volumes remain high and there is limited substitution to domestically produced alternatives.

There is no doubting the scale of the ambition to reshape the US economic outlook, but the historical record suggests that attempting to achieve mutually inconsistent objectives is unlikely to be successful.

Recommended content for you

Learn more about our business

We are one of the world's largest asset managers, with capabilities across asset classes to meet our clients' objectives and a longstanding commitment to responsible investing.