Disclaimer: Views in this blog do not promote, and are not directly connected to any L&G product or service. Views are from a range of L&G investment professionals, may be specific to an author’s particular investment region or desk, and do not necessarily reflect the views of L&G. For investment professionals only.

An end to US exceptionalism?

The rebalancing to come, messy though it may be, could ultimately lead to a healthier equilibrium of capital allocation.

The following is an excerpt from our midyear global outlook.

The US enjoys tremendous advantages with its enormous, c. $30 trillion single market.[1] As investors reappraise their holdings in US dollar assets, can the world’s largest economy sustain the exceptionalism that has defined it in recent years?

Currently, the country’s free-market system encourages innovation and entrepreneurship, with deep capital markets providing funding and elite universities attracting top talent from around the world. It is the global technological leader and home to the largest companies in the world. In addition, the US has access to cheap abundant energy, which allows it to be self-sufficient; holds the global reserve currency; and has unmatched military power.

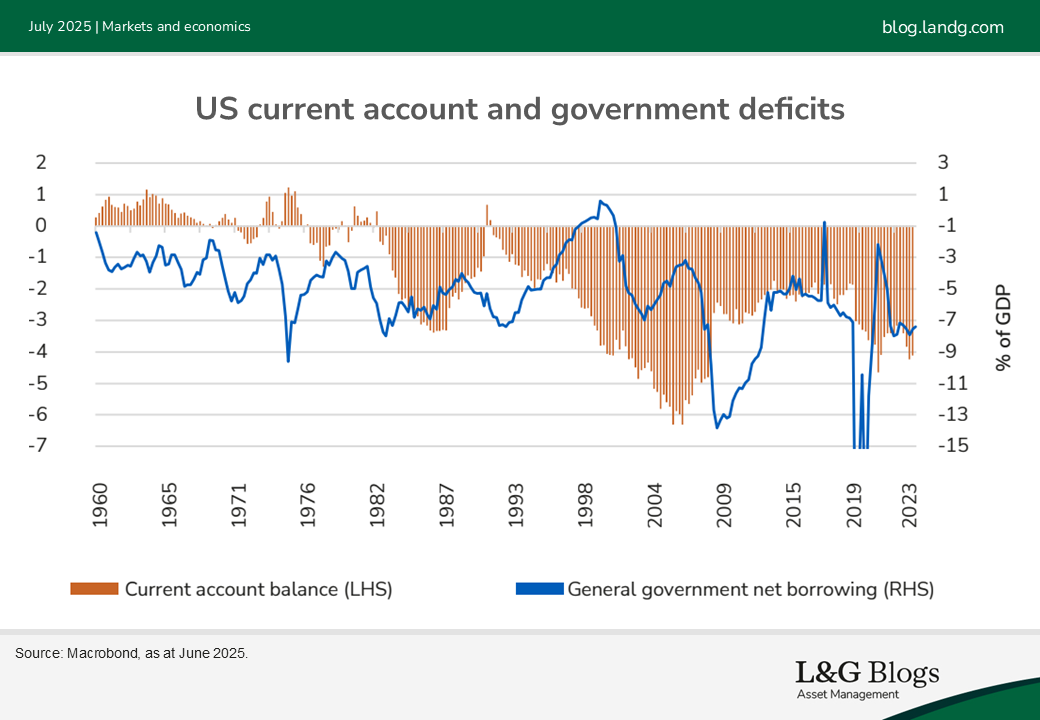

These features have historically allowed the US to attract strong capital inflows. However, there is an inherent paradox associated with being the issuer of the global reserve currency. As a matter of arithmetic, net capital inflows must be matched by a current account deficit and entail accruing liabilities to foreigners. That imbalance is a product of the inherent strengths of the US economy but, when sustained for long periods of time, creates a source of vulnerability.

The twin current-account and fiscal deficits in the US are borne out of its reserve currency status, but also risk undermining it if we are past the point of peak enthusiasm for US assets.

Recently foreign investors have become unsure of the direction of domestic policy. The Trump administration has a number of priorities, some of which are potentially in tension. For example, there is a clear desire to reduce the persistent US trade deficit, but tax cuts might boost demand, add to fiscal deficits and increase imports.

Similarly, are tariffs mainly a negotiating tool for more favourable trade deals, a mechanism to raise revenues or an attempt to onshore production? To restore US manufacturing competitiveness, import prices would likely have to rise significantly. This could trigger a broader increase in inflation and put upward pressure on interest rates. A manufacturing renaissance could crowd out private sector services, while higher interest rates add to concerns about public sector debt dynamics.

Investor questions

In addition, some foreign investors have begun to question US global leadership, its commitment to multilateral institutions and the architecture it has built over the last seventy years. There is also concern about the agenda to remove some of the constraints on executive authority and the erosion of the independence of US institutions. With Congress losing influence in the current political dynamic, the judiciary has a more central role in providing checks and balances. A recent ruling confirmed the independence of the Federal Reserve’s (Fed) leadership, which has helped reassure markets.

The US is a highly financialised economy. This is a great strength, but also makes it particularly sensitive to a deterioration in market sentiment. We have already seen an adverse market reaction which ultimately tempered the more extreme tariffs announced on ‘Liberation Day’. While the US has enjoyed tremendous flexibility to deploy fiscal policy to offset shocks, this might be reaching its limit.

It is hard to know exactly when and what will be the trigger for the bond market to force discipline on Washington, but deficits of 6-7% of GDP[2] in an economy at full employment is a weak starting point. Add in rising interest payments, and the pressure on mandatory spending from an ageing population, and it is clear fiscal policy is on an unsustainable path – with Moody’s projecting debt to GDP to rise from 98% last year to 134% by 2035.

In the near term, we expect underlying growth to slow as price rises from tariffs squeeze real incomes and policy uncertainty undermines business investment. However, the consensus among economists is that the US should be able to skirt recession. Medium-term potential growth is likely to be lower as immigration policy slows labour supply.

Sustaining American exceptionalism – both in terms of economic outcomes and asset price performance – will likely require the US to adopt and embed the use of artificial intelligence as a labour-augmenting (and potentially labour-replacing) innovation. The US seems best placed to embrace that technological leap forward; whether it will be enough to counterbalance the offsetting downward pressures on growth is the pivotal question going forwards.

A new equilibrium

Whether the US can remain the preeminent worldwide destination for global capital remains to be seen, particularly as some members of the current administration have argued that too much foreign capital has been chasing too few US assets, for too long.

These policymakers are not only aiming to reduce trade deficits and by extension the capital account, but had been threatening to pursue direct taxes on foreign capital. Section 899 has now been removed from the ‘Big Beautiful Bill’. This still leaves uncertain consequences from this and future attempts to fundamentally reshape global capital flows at a time of large fiscal deficits.

There is no doubt that foreign investors are beginning to think carefully about their US exposure as a consequence of the last six months. Already, US exposure in global equity indices presents an over-concentration challenge at 60-70%.[3] That said, there is evidence that total holdings of US assets by foreigners is substantially lower, at an average of 10-20%.[4]

Still, global allocators of capital will likely take a more cautious approach to increasing their US exposure, at the very least. Structurally, the EU and UK seem most likely to be key beneficiaries at the expense of the US, particularly as increased defence spending increases deficits and thus the need for capital inflows.

For US markets, the suggestion is that a relative minor shift in the marginal buyer of various US assets could result in higher risk premiums and a reduction in the – admittedly difficult to quantify – uplift that US markets have enjoyed relative to the rest of the world. If so, the rebalancing to come, messy though it may be, could ultimately lead to a healthier equilibrium of capital allocation – one where capital and returns are more evenly shared.

This article is an excerpt from our midyear global outlook.

[1] Source: GDP (current US$) - United States | Data

[2] Source: Federal Surplus or Deficit [-] as Percent of Gross Domestic Product (FYFSGDA188S) | FRED | St. Louis Fed

[3] Source: US weighting in MSCI World index is c. 71% as of May 2025

[4] See, for example, J.P.Morgan report ‘Do foreign investors hold too much of US assets?’, May 2025.

Recommended content for you

Learn more about our business

We are one of the world's largest asset managers, with capabilities across asset classes to meet our clients' objectives and a longstanding commitment to responsible investing.