Disclaimer: Views in this blog do not promote, and are not directly connected to any L&G product or service. Views are from a range of L&G investment professionals, may be specific to an author’s particular investment region or desk, and do not necessarily reflect the views of L&G. For investment professionals only.

The evolution of commodity investing: from ancient Sumer to BCOM

In the first instalment of a two-part series, we delve into the origins of commodity futures markets, and the developments that paved the way for the first generation of broad commodity indices.

Among the most intriguing artefacts of the ancient Sumerian civilisation are ‘bulla’: sealed clay vessels containing intricate tokens representing livestock and crops.

Historians believe these objects are the physical embodiment of the conceptual shift from an economy based on barter to standardised, tokenised trading.1 Found alongside bulla are tablets inscribed with delivery dates later than the point of sale, suggesting futures markets have existed in one shape or another since the dawn of human civilisation.

These nascent markets played a vital role in mitigating the perilous uncertainty facing the farmers and herders from the fourth millennium BC, but investors wishing to access the potential diversification* and inflation hedging benefits of commodities would have to wait a little longer.

Laying the groundwork

With the exception of precious metals, the storage and transportation of bulky, perishable goods mean direct physical investment in commodities is impractical for the vast majority of investors.

However, by the 1500s the Amsterdam Stock Exchange – which was a commodities exchange before becoming a stock exchange – had reached a level of sophistication that enabled investors to gain exposure to changes in the prices of certain commodities without having to take possession of them.2

In the 19th and 20th centuries, the US would emerge as the leading centre of innovation in commodities markets. Established in 1864, the Chicago Board of Trade did much to standardise definitions of various commodities, leading to the creation of detailed standards for commodities such as soybeans.3

This in turn paved the way for the US government’s Commodity Price Index, which became publicly available in 1940.

First-generation commodity indices

1991 saw the launch of the S&P GSCI index, the first major investable commodity index. Funds tracking this index, and following ones such as the Bloomberg Commodity Index (BCOM), opened the doors to commodity investing for ordinary investors by providing a straightforward way of gaining exposure to changes in price among a broad basket of commodities.

This also coincided with the launch of the first ETFs, providing a low-cost, transparent and liquid vehicle for various types of investors.

The construction of first-generation commodity indices owed much to the methodology adopted for market-cap-weighted equity indices, aiming at straightforward replication achieved via a static process.

This is evident in two specific areas: the approach to rebalancing and the approach to contract selection.

The weights of the various commodities within these indices are fixed at regular intervals, annually in the case of both GSCI and BCOM. Secondly, these first-generation indices were intended to track the spot price of the underlying commodities as closely as possible, so invested as near as possible to the front month of the futures curve. This results in frequent rolling, typically every one or two months.

Limitations of the static approach

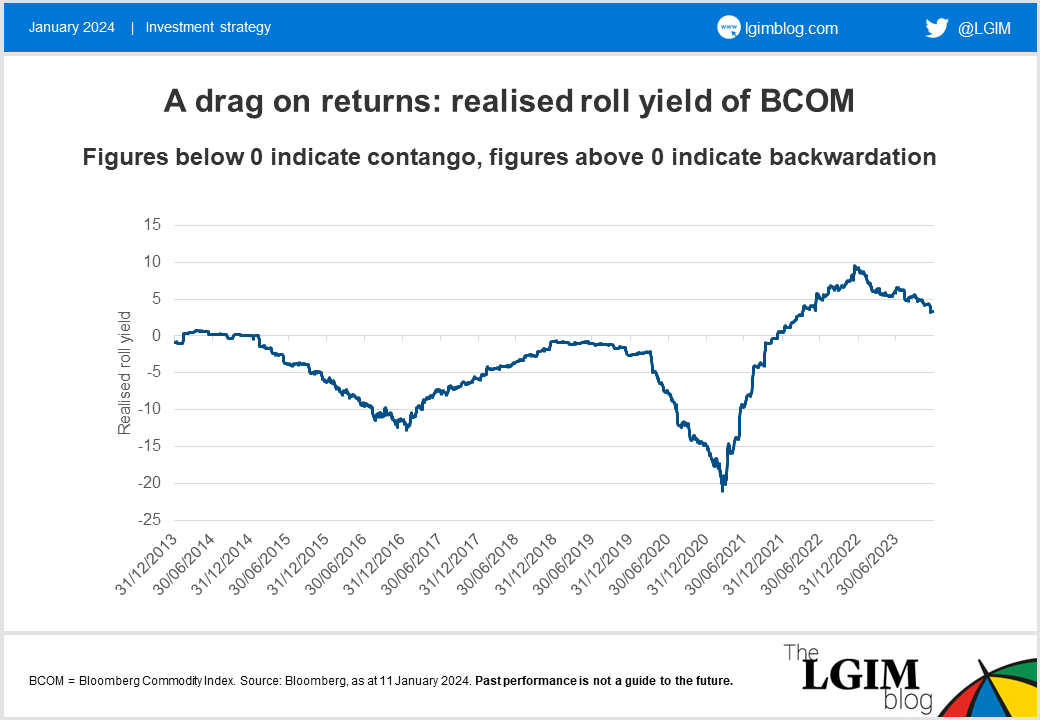

This static approach to contract selection carries the potential cost of negative roll return when near-delivery months are in contango, and potentially misses the positive returns that might be generated via a dynamic approach that aims to capitalise on backwardation.

The chart below shows that over the past decade, the roll return of BCOM has acted as a drag on overall returns for the majority of that period.

Over the decade following the launch of the first generation of broad commodity indices awareness of these drawbacks increased, leading to the development of a second generation of indices.

The long history of commodity trading would help inform the construction of this new breed of indices, providing compelling historical evidence of differing characteristics among the various constituents of a broad commodity basket that could potentially be targeted by a more dynamic approach to the futures curve.

In the second part of this blog, we’ll examine how this new generation of broad commodity indices aim to overcome the shortcomings of their predecessors, and their potential use in diversified multi-asset portfolios.

*It should be noted that diversification is no guarantee against a loss in a declining market.

1. Source: https://sites.utexas.edu/dsb/tokens/tokens/

3. Source: Subpart J -- United States Standards for Soybeans (usda.gov)

Recommended content for you

Learn more about our business

We are one of the world's largest asset managers, with capabilities across asset classes to meet our clients' objectives and a longstanding commitment to responsible investing.