Disclaimer: Views in this blog do not promote, and are not directly connected to any L&G product or service. Views are from a range of L&G investment professionals, may be specific to an author’s particular investment region or desk, and do not necessarily reflect the views of L&G. For investment professionals only.

Where’s the beef?

How the US beef industry can navigate the climate transition.

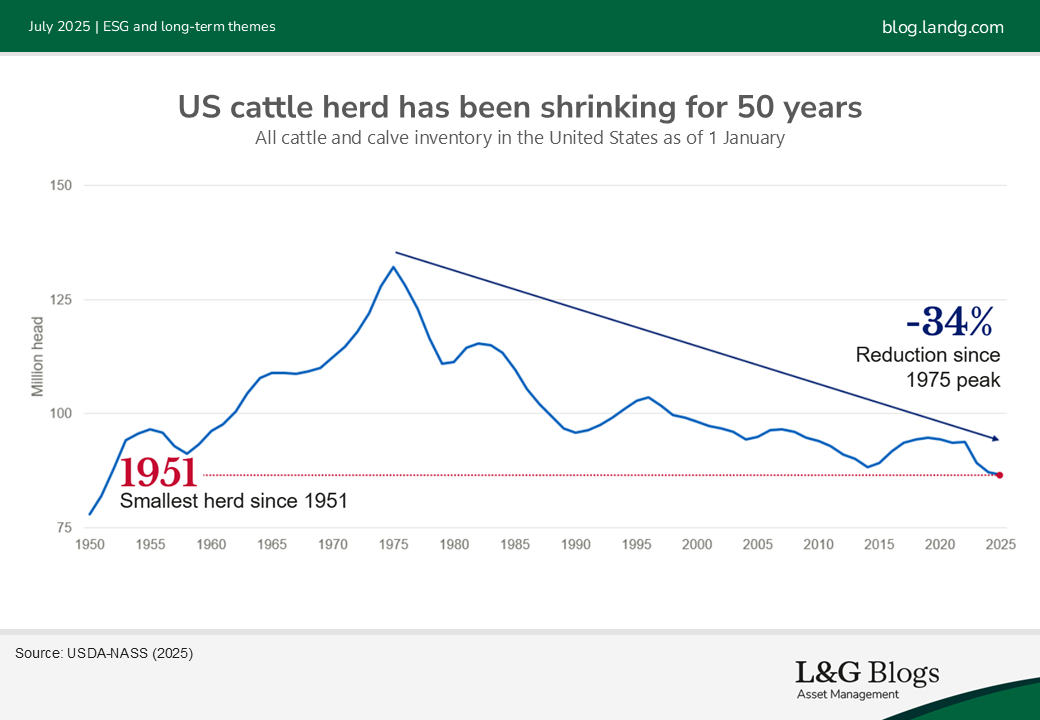

The US beef industry is facing a moment of reckoning. With herd sizes at their lowest since the 1950s and climate volatility rising, producers and investors alike are asking: is this just another cycle – or the beginning of a new normal?

At the heart of this question lies a deeper tension. Beef is both a driver of climate change and increasingly a victim of it. Understanding this dual role is essential for navigating the risks – and seizing the opportunities – that lie ahead.

Beef’s outsized role in the climate story

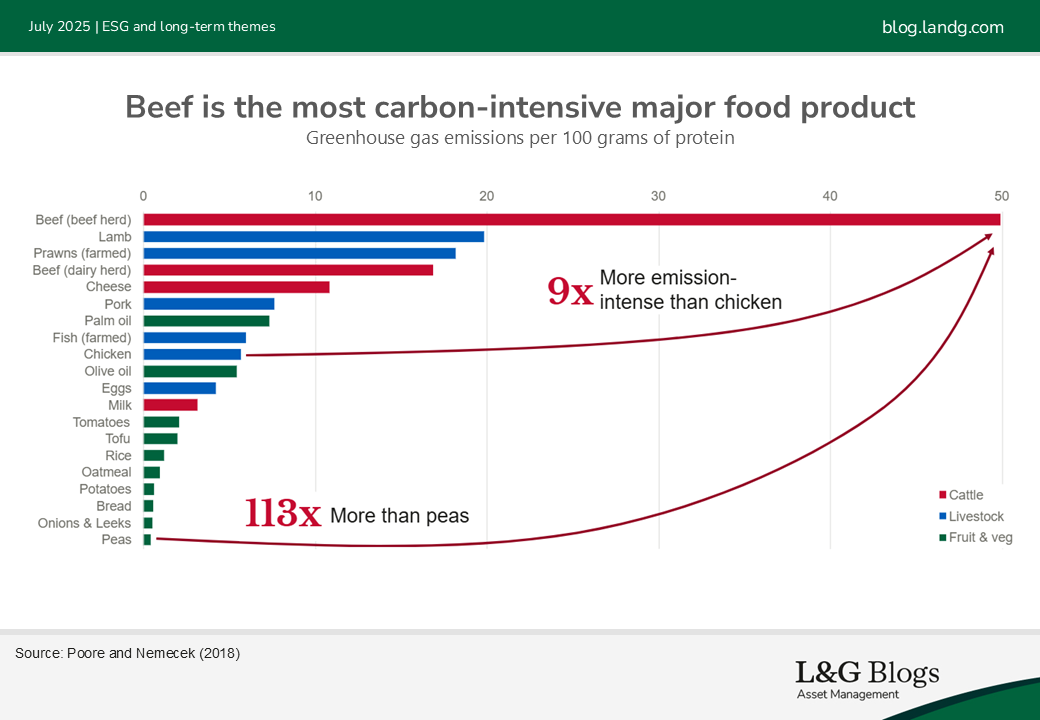

Food systems account for roughly a third of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, and beef is the most emissions-intensive major food product – something like 9x more than chicken and over 100x protein from peas.[1] The reasons are well known: methane from enteric fermentation (otherwise known as cow burps), land-use change for grazing and feed, and the inherent inefficiency of converting plants into animal protein.

Methane (CH4) represents around 60% of cattle emissions and plays a significant role in short-term climate policy. While CO2 lingers in the atmosphere for centuries, CH4 lasts about a decade. It is ~27 times more potent than CO2 over 100 years (global warming potential, or GWP-100), but 80 times more impactful when considered over 20 years (GWP-20).[2]

This short-lived, high-impact nature means reducing CH4 emissions now can greatly benefit the near-term climate and help keep us below potentially dangerous tipping points. On a GWP-20 basis, global cattle emissions would be on-par with the highest-emitting nations – second only to China.[3]

Interestingly – and perhaps less appreciated than the overall climate challenge of beef – is how highly varied impacts can be across producers, even within similar geographies. The GHG emissions and land use of beef producers in the worst 10% are 12 and 50 times larger than the best 10%, respectively.[4] This disparity suggests plenty of opportunity of targeted intervention, to help make a big problem more manageable.

But the relationship runs both ways. Climate change is also reshaping the operating environment for beef and dairy producers. Cattle are sensitive to heat stress, with optimal temperatures around 20°C. When temperatures rise, cows eat less, grow more slowly, and become more susceptible to disease. In the US dairy sector alone, heat stress cost an estimated US$1.8 billion in 2010.[5] By 2045, similar dynamics could reduce the value of US beef production by 5–7%.[6]

Droughts cause further challenges. They reduce the availability of pasture, forcing ranchers to buy supplemental feed – the price of which is also increasingly volatile due to extreme weather. These droughts are expected to become longer, more frequent, and more severe, particularly in key cattle-rearing regions. The USDA anticipates payouts from the Livestock Forage Disaster Program – which compensates producers for grazing losses – could more than double over the next 50 years.[7]

An unprecedented cycle — or a new normal?

The current downturn in US beef production is not just cyclical. It reflects a convergence of climate, demographic, and economic pressures that may permanently reshape the industry.

The COVID-era supply shock, combined with prolonged drought and feed price volatility, has left deep scars. But at the same time, the industry faces broader structural headwinds:

- Aging producers: Nearly 40% of US farm operators are over 65, compared to around 20% at the turn of the century

- Waning domestic demand: Americans eat an average of 25kg of beef a year each – still more than almost any other country, but significantly below the 40kg peak of the 1970s[8]

- High operating costs: Unlike previous cycles, today’s environment lacks the low-interest rate tailwind that once supported herd expansion, and other costs such as labour are up too

Despite record-high beef prices, there is only limited evidence of heifer retention so far — a traditional signal of herd rebuilding. Even once that changes, it takes 2–3 years to raise a cow to market weight. In the meantime, supply will remain tight, and volatility high.

Industry analysts increasingly suggest that we may be entering a ‘new normal’ of structurally lower supply and elevated prices. For meat packers – whose margins depend on throughput – this presents a strategic dilemma. The traditional ‘control the controllables’ approach, focused on efficiency and waiting for the cycle to turn, is a sensible approach at any point in the cattle cycle. However, it may no longer be fit for purpose when thinking about the longer term.

Designing a new playbook

So how should the industry respond?

While beef and dairy are likely to remain part of many diets for decades to come, we may be returning to a world where beef is an occasional luxury, not an everyday staple. The good news is that the industry has already shown it can adapt. Over the past 20 years, the share of Prime-grade US beef has tripled, Prime & Choice now account for 85% of production.[9] Consumers have shown they are willing to pay more – if the quality is there.

To build on this momentum, producers and processors could consider three strategic shifts:

1. Lean into premiumisation

As supply tightens and prices rise, consumers will demand more from every cut. A premiumisation strategy – focused on quality, health, animal welfare, and environmental stewardship – can help justify higher prices and build brand loyalty, even in a potentially shrinking market.[10]

2. Strengthen supply chain resilience

Premiumisation must be underpinned by a robust, transparent supply chain. That means supporting ranchers to adopt sustainable practices – such as regenerative grazing or methane-reducing feed additives – and investing in tracking and certification systems that can verify claims and build trust with retailers and consumers.

As noted above, the environmental impacts of beef are highly variable, depending on farming practices and other factors. This means overall impacts can be skewed by the worst performing producers a supply chain – the worst quarter of beef herds globally represent 56% of GHG emissions and 61% of land use.[11] This implies substantial potential to reduce environmental impacts and enhance productivity in the food system by targeting simple low-hanging fruit measures to get everyone up to standard.

3. Diversify capital investment

With beef margins under pressure, it may make sense to reallocate capital toward higher-growth, higher-margin segments. Chicken, for example, continues to gain market share due to its lower cost, lower health costs than red meat, and smaller environmental footprint. The chicken sandwich wars of recent years reflect this shift in consumer preference.

Alternative proteins, while no longer in the hype phase of 2020–21, also present long-term growth potential. Europe remains the world’s largest market, and retail sales continue to expand. For diversified protein companies, could these trends offer a hedge against beef volatility and a pathway to future growth?

Resilience through reinvention

The US beef industry has shown remarkable resilience in the face of past disruptions. But the challenges it now faces – from climate volatility to demographic and preference shifts – are unprecedented in scale and duration.

Still, this does not have to be a story of decline, but one of reinvention. By embracing premiumisation, investing in supply chain resilience, and diversifying strategically, the industry can not only weather the storm – it can emerge stronger, more sustainable, and more aligned with the expectations of tomorrow’s consumers and investors.

The question is no longer whether change is coming. It’s whether the industry is ready to lead it.

Assumptions, opinions, and estimates are provided for illustrative purposes only. There is no guarantee that any forecasts made will come to pass. Whilst L&G has integrated Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) considerations into its investment decision-making and stewardship practices, this does not guarantee the achievement of responsible investing goals within funds that do not include specific ESG goals within their objectives.

[1] Poore & Nemecek (2019) Reducing food’s environmental impacts through producers and consumers

[2] IPCC AR6 WG1 (2021) Chapter 7: The Earth’s Energy Budget, Climate Feedbacks and Climate Sensitivity

[3] McKinsey (2020) Agriculture and Climate Change

[4] Poore & Nemecek (2019) Reducing food’s environmental impacts through producers and consumers

[5] Converted to 2025 USD. USDA (2014) Climate Change, Heat Stress, and U.S. Dairy Production

[6] Thornton et al. (2022) Impacts of heat stress on global cattle production during the 21st century: a modelling study

[7] USDA (2024) The Stocking Impact and Financial-Climate Risk of the Livestock Forage Disaster Program

[8] Boneless retail weight. USDA (2025) Livestock and Meat Domestic Data

[9] USDA (2025) Agricultural Marketing Service

[10] For example, adding sustainability claims to products consistently yields significant benefit, expanding brand reach and appeal. NYU Stern & Edelman (2023) Effective Sustainability Communications

[11] Poore & Nemecek (2019) Reducing food’s environmental impacts through producers and consumers

Recommended content for you

Learn more about our business

We are one of the world's largest asset managers, with capabilities across asset classes to meet our clients' objectives and a longstanding commitment to responsible investing.