Disclaimer: Views in this blog do not promote, and are not directly connected to any L&G product or service. Views are from a range of L&G investment professionals, may be specific to an author’s particular investment region or desk, and do not necessarily reflect the views of L&G. For investment professionals only.

Water you waiting for? Rethinking our approach to water management

Freshwater ecosystems are degrading. Could a new approach that appreciates the hydrological cycle hold the answer?

Earlier this year, California dominated global headlines when devastating fires swept through large parts of Los Angeles. The availability of water became a focal point of discussions across California and the government.

While it's common to react to visible water crises, policy and corporate approach often focuses too much on visible 'blue water'. 'Green water' – the invisible water stored in soil and plants – is often overlooked, as is the extent to which land-use decisions are impacting the wider hydrological cycle.

What does that mean?

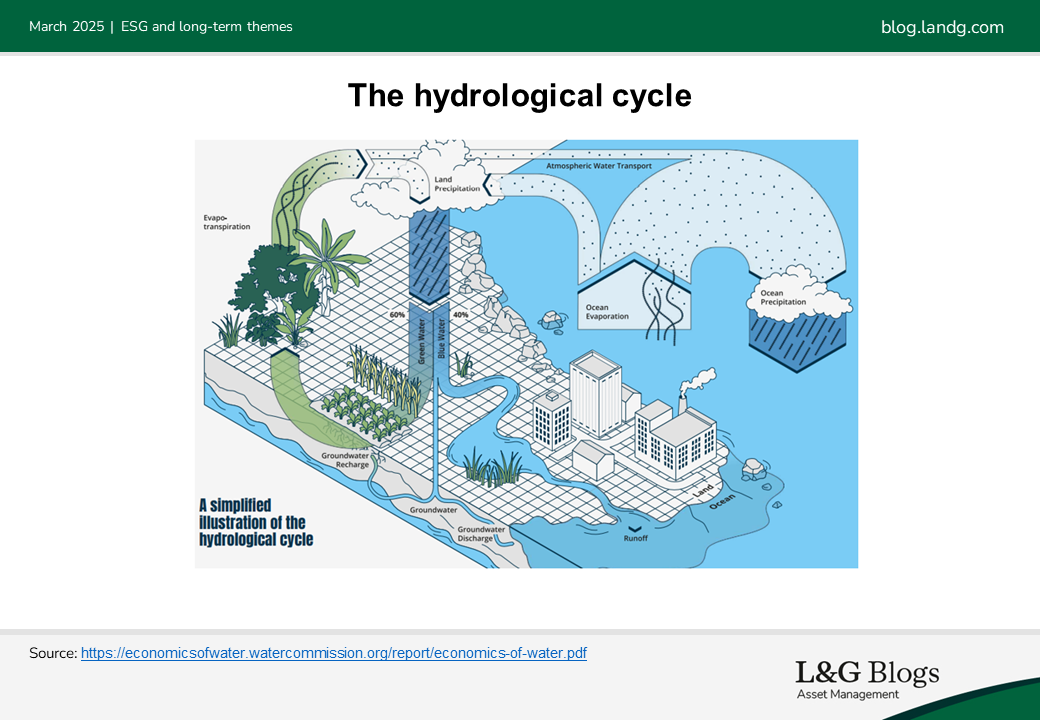

Freshwater originates from precipitation, and when it falls over land, it is categorised into two interconnected areas: blue water (visible) and green water (invisible). Blue water includes runoff that becomes groundwater, and surface water, such as rivers, wetlands, lakes, and aquifers. Green water, on the other hand, is rainfall stored in the soil or vegetation[1].

Unsurprisingly, most of our attention is on blue water. It is measurable, visible, and difficult to ignore. Blue water is essential to industries like agriculture, manufacturing, and energy. It forms the basis of aquatic ecosystems and is commonly extracted by humans and industry.

The UN Environment Programme warns that half of the world's freshwater ecosystems are degrading [2]. Blue water quality and quantity are increasingly impacted by over-extraction, pollution, and ecosystem degradation. For example, over 80%[3] of wastewater globally is released untreated.

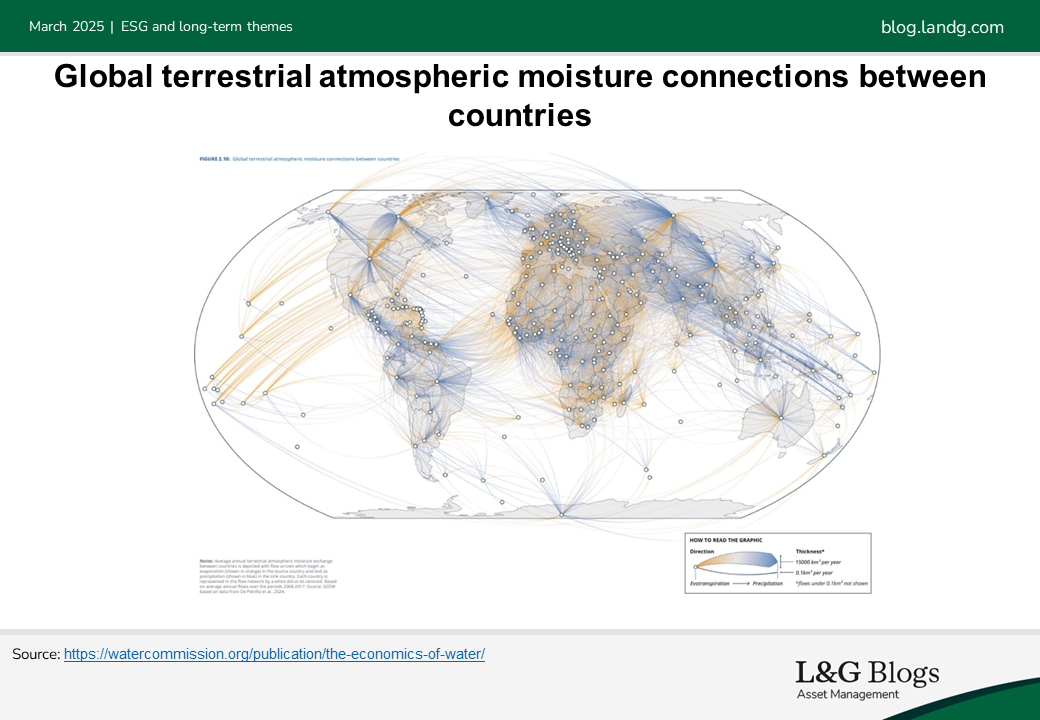

Green water is less visible, indirect, and globally connected. This often means it is overlooked when we attempt to understand our impacts, dependencies, and risks associated with water. It also means that we may not consider the implications on the hydrological cycle when land-use changes are made.

Green water plays a fundamental role in the hydrological cycle, with 60% of precipitation falling on land going to green water[4]. It’s central to the strength of our food system, maintaining healthy terrestrial ecosystems, and key to resilience against droughts.

As the degradation of nature continues and climate change intensifies, the availability of green water is becoming less reliable. Droughts and floods exacerbate soil erosion and land degradation, creating vicious cycles: less fertile soil that cannot support vegetation or absorb rainfall, more green water lost, more land deforested for agriculture, and more intense forest fires.

Indeed, forests play an important role in green water management. They regulate flow by absorbing or releasing water when required and influence local rainfall patterns. The World Bank found that the impacts of dry shocks (periods of intense drought) are more severe in regions with local and upstream deforestation. This highlights the interconnectedness of green water and the indirect impacts of land-use change, including deforestation. The impact on green water in land-use decisions should be considered to protect evapotranspiration[5] hotspots such as forests, wetlands, and watersheds[6].

Less reliable green water poses particular risks for companies in the agribusiness, food (rain-fed crops), and energy sectors (biomass particularly). For example, the coffee industry is highly dependent on consistent green water availability. Coffee plants require specific moisture levels in the soil to thrive, and fluctuations in green water can lead to reduced yields and lower quality beans.

Corporates that fail to understand their dependence and impact on green water may face more volatile supply chains and increased operational costs. In the agricultural sector, practices such as soil moisture retention, drought-resistant crops, and regenerative farming practices could help address these challenges.

Beyond agriculture, the loss of green water availability can lead to the collapse of natural systems that provide ecosystem services including carbon sequestration, flood control, and water purification.

Stakeholders are starting to take note. The Stockholm Resilience Centre (SRC) has recently categorised their ‘freshwater change’ planetary boundary into blue and green water, with both categories having crossed limits, heightening the risk of abrupt or irreversible environmental shifts. The recent Global Commission on the Economics of Water has also highlighted the underappreciation of green water[7].

Embracing a holistic approach to water management

To create and maintain long-term value for our clients, it’s imperative to broaden our collective approach to water management, both at a corporate and policy level, and strengthen how we account for land-use decisions that impact the hydrological cycle. We need a proactive and holistic approach to managing both blue and green water. Corporates and policymakers must recognise the interconnectedness of terrestrial and aquatic practices and their transboundary impacts, appreciating the entire hydrological cycle.

Conducting water footprinting analysis and adopting frameworks like the Taskforce for Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD) can support corporates in understanding and addressing water issues. However, further efforts and international collaboration are needed by policymakers to develop adaptive and comprehensive strategies for water-related challenges.

For investors who choose to access the clean water theme via equities, we believe a holistic approach may also be valuable. While utilities are the obvious way to gain exposure, innovators from across the water management industry are using cutting-edge technology, including artificial intelligence, to increase efficiency and reduce water loss. With global water supplies under increasing stress, we believe that technology innovations and solutions combined with investment in infrastructure and stronger regulation and enforcement, as explained in our report, will be critical in the years to come.

[1] Water can move below and reach the water table and then groundwater, becoming blue water. https://economicsofwater.watercommission.org/report/economics-of-water.pdf

[2] https://wedocs.unep.org/handle/20.500.11822/46105

[3] https://www.unwater.org/sites/default/files/app/uploads/2018/10/WaterFacts_water_and_watewater_sep2018.pdf

[4] https://economicsofwater.watercommission.org/report/economics-of-water.pdf

[5] Evapotranspiration is the combined loss of water in the form of evaporation from the soil surface and transpiration from the plan.

[6] https://watercommission.org/publications/

[7] https://watercommission.org/

Recommended content for you

Learn more about our business

We are one of the world's largest asset managers, with capabilities across asset classes to meet our clients' objectives and a longstanding commitment to responsible investing.