Disclaimer: Views in this blog do not promote, and are not directly connected to any L&G product or service. Views are from a range of L&G investment professionals, may be specific to an author’s particular investment region or desk, and do not necessarily reflect the views of L&G. For investment professionals only.

How could the oil sector navigate the energy transition?

Few industries are as exposed to the energy transition as oil. What options does it face in a future of uncertain demand?

Over the last ten years, oil and gas equities have underperformed global stocks by more than 40%. They’ve also fallen from making up around 6.5% of the S&P 500 in 2015 to around 3% today[1], with some oil companies performing significantly worse than that average. While the sector plays an important diversification role in portfolio management, this under-performance remains an issue.

Unsurprisingly many commentators are asking not only why this has occurred, but how the industry should respond. To answer that question, it’s worth stepping back and thinking about what drives either share price over or under-performance over long periods of time.

In our view, three factors explain stock price performances over the long term: the market’s assessment of near-term earnings and cash generation, implied long-term (sometimes called ‘terminal’) earnings growth, and relative earnings volatility (normally expressed as a company’s cost of capital).

The first factor is the market’s confidence in a company’s ability to grow its earnings and cash flows over the forward-looking timespans that most equity analysts try to forecast – typically 3-5 years. The second is more nebulous, but is typically the market’s long-term view on the durability of earnings growth that a company may be able to generate over a longer period. The third is the riskiness, or volatility, in a company’s earnings through the business cycle, especially considering its balance sheet. Balancing these three factors could be considered the three pillars of sustainable equity market outperformance.

An uncertain future

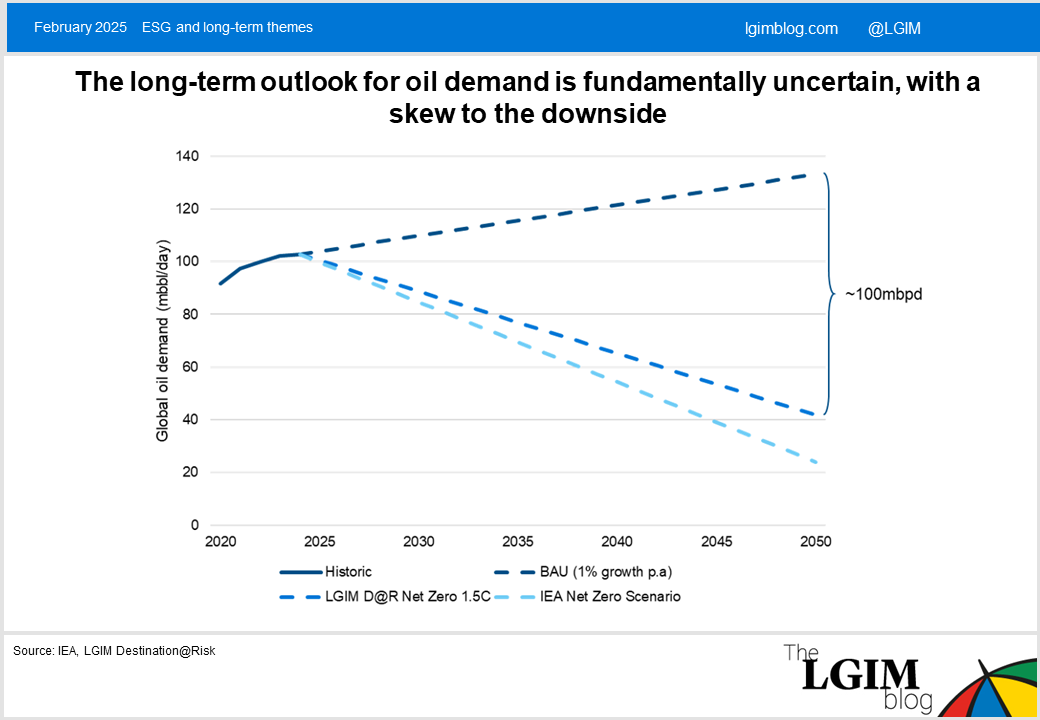

Oil is the most important commodity in the world. At present, global demand for oil products is over 100 million barrels per day[2]. Our own research suggests that over the next 25 years, it is possible that demand might grow by as much 50 million barrels per day; alternatively, it could contract by about the same margin.

In other words, global oil markets face a plausible window of uncertainty equivalent to roughly 100% of today’s entire global market. This is unprecedented. However, the probability of both ends of this range being realised are not equal – with the long-term risks skewed, in our view, to the lower end of this range.

Regardless of our views on the politics, or the level of commitment to the policy imperative, we see the energy transition as an inevitable reality. The resulting long-term uncertainty has created a huge strategic dilemma for the industry, calling into question at least two of our value creation levers.

On the one hand, a plateau in demand for oil followed by a subsequent decline would imply an increase in oil price volatility and an increase in the risk of investing in the oil and gas industry. On the other is the long-term growth component – here too the energy transition raises real questions. If demand for an industry’s primary product faces medium and long-term decline, how can the market ascribe a positive long-term growth rate to this industry’s equities?

Three routes forward

We think there are three plausible responses the industry can take to this challenge.

The first of these is the strategy we call the ‘ostrich’. An oil company can stick its head in the sand and pretend nothing is going to change. An ostrich will continue to invest in its core business and take no steps at all to try and respond to the challenges that lie ahead. The result is a maximisation of near-term earnings (our first factor), at the expense of a falling long-term growth rate and a commensurate increase in implied earnings volatility.

The second plausible strategy is one that we call the ‘ATM’. By committing to a strategy of managed gradual decline in supply, energy companies can quite plausibly deliver attractive cash returns to shareholders by investing progressively less in their core businesses and returning more cash to shareholders. Management teams can focus on accumulating market share and capitalising on significant economies of scale – this is a reasonable strategy to maximize shareholder value in areas of distinct competitive advantage. This strategy has the potential to be a highly attractive one to investors, but depends on a management team demonstrating real discipline – especially through cycles.

The third plausible strategy is one of total reinvention.

This is a path less travelled by the industry – and, for a few companies, one that has proven volatile and unpredictable. It involves deep and thoughtful evaluation of the genuine sustainable competitive advantages of any given company – with a keen eye to the challenges and huge uncertainties that lie ahead through the energy transition. This is then followed by a ruthless process of reinvention: transforming the core business into one that stands not only to survive, but to thrive amid the energy transition that lies ahead. This pathway has the potential to create both long term value at the same time as making a materially positive contribution to global decarbonisation. However, pursuing this pathway requires a difficult balancing act between near-term earnings (factor one) and the long-term growth rate.

In the short term, reinvention involves significant uncertainty in a company’s near-term earnings. It involves real thinking about where a company’s competitive advantage lies – especially given the challenges of decarbonising the world. It requires deep conviction in a management team in the face of this uncertainty and a clarity of strategic thought – to demonstrate how reinvention will lead to sustainable earnings growth, rather than simply target the areas with the fastest revenue growth potential with no concerns for return profiles. Only then will management teams build market confidence in the strategy and show it will lead to a better outcome for shareholders than simply shrinking the company over time and returning the cash proceeds to investors.

What is clear to us is that - regardless of how short term the focus of equity markets may be - pursuing the ostrich strategy is not a viable one for a business that wishes to thrive over the long term.

Today, most are failing to articulate a clear answer to this question – and as companies move to present investors with their answers to these problems, it is by this yard stick that we will judge their success or failure. Can any oil company articulate a clear, compelling, return-focused case as to how they will not only survive but thrive as the energy transition accelerates – or will they simply accept a future of inevitable decline, managed or otherwise?

[1] Source: Bloomberg as at 25 February 2025

[2] Source: IEA as at 25 February 2025

Recommended content for you

Learn more about our business

We are one of the world's largest asset managers, with capabilities across asset classes to meet our clients' objectives and a longstanding commitment to responsible investing.